![]()

Bacterias del Suelo y Erosión Eólica

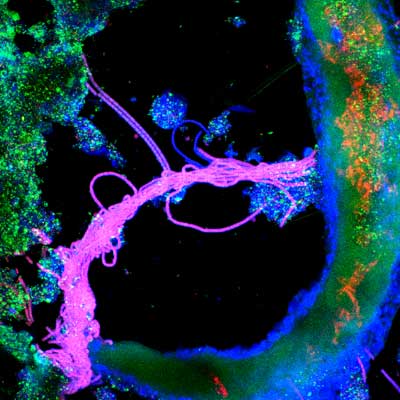

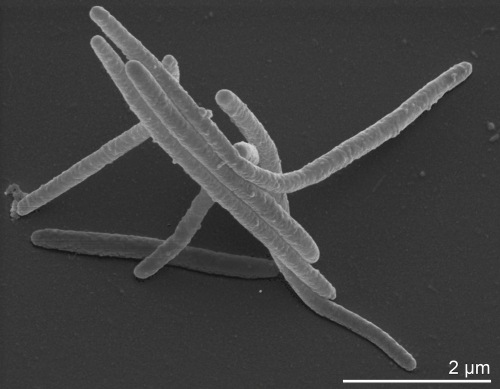

Mediante técnicas de Pirosecuenciación y haciendo uso de túneles de viento, investigaciones recientes han mostrado el efecto de la erosión eólica de diferente intensidad sobre el arrastre partículas del suelo de diferente tamaño, así como el tipo de las bacterias que eran arrancadas del suelo. La Pirosecuenciación sirve con vistas a determinar el DNA global de las muestras, permitiendo discernir entre los distintos de los grandes grupos bacterianos. Por su parte, los de túneles de viento se ha utilizado con el propósito de simular el arrastre de materiales (inorgánicos, orgánicos y biogénicos) bajo diferente regímenes de viento sobre tipos de suelos y sedimentos de naturaleza variada. Así se ha podido demostrar que las comunidades bacterianas que albergan las partículas de mayor tamaño son distintas de las contenidas en las de menor calibre. Del hecho, según los autores, se demuestra que estos diferentes micro-hábitats atesoran comunidades distintas, por lo que según el viento arrastre uno u otro tipo de partículas también exportará a otros lugares en donde se depositen microrganismos diferentes, empobreciendo los horizontes superficiales del suelo en unos u otros. Cabe recordar que distintas clases de bacterias desempeñan diferentes roles en el medio edáfico, por lo que resulta interesante conocer cuales son más susceptibles de volar a otros lares, según las condiciones ambientales y edafotaxa que se den en un determinado enclave, afectando al metabolismo del suelo de manera diferencial. Así por ejemplo, las Proteobacteria, que desempeñan un papel sumamente importante en los ciclos del carbono y el nitrógeno, aparecen fundamentalmente asociadas a las fracciones granulométricas gruesas del suelo. Por el contrario, las fracciones finas se caracterizan por la gran cantidad que atesoran de Bacteroidetes y otros microbios muy resistentes a condiciones extremas, tales como la sequedad o la alta incidencia de radiaciones gama. También cabe recordar que la exportación por el viento afecta de manera diferente a las partículas del suelo en función de su tamaño. Las mayores, por su peso, caen rápidamente a tierra, por lo que apenas suelen distanciarse del lugar de donde fueron erosionadas, mientas que las finas pueden viajar suspendidas en el aíre y ser depositadas a cientos o miles de kilómetros de distancia, lo cual encaja con las propiedades previamente mentadas. En base a estos hallazgos, los investigadores que llevaron a cabo este estudio defienden que la superficie del suelo afectada por la erosión eólica pierde diversidad microbiana, aunque de forma diferencial. Del mismo modo, las Actinobacterias también muy importantes en el metabolismo del medio edáfico, y la formación de esas estructuras denominadas agregados, suelen resistir la acción del viento permaneciendo arraigadas al lugar donde nacieron. Con independencia de los suelos bajo condiciones naturales áridas y semiáridas, que suelen padecer frecuentemente de la falta de cobertura vegetal, una gran parte de las tierras agrícolas del mundo, durante alguna estación permanecen desnudas, siendo fácil presa de la erosión cuando las condiciones meteorológicas la propician.

Proteobacterias. Fuente: Universidad de Auckland

Finalmente, este tipo de análisis, según los autores, pueden servir tanto, para entender la huella digital microbiana tras un impacto ambiental y así evaluar sus repercusiones, como reconocer la importancia de enriquecer el suelo en materia en materia orgánica, mediante una gestión adecuada que evite o minimice el tiempo en el que el suelo se encuentra desnudo y evitar la perdida de microrganismos que pueden afectar negativamente a la hora de que el medio edáfico mantenga un metabolismo saludable. El estudio me parece interesante y original, en especial por utilizar los túneles de viento para simular regímenes de perturbación del medio edáfico bajo condiciones meteorológicas dispares. Ahora bien, aun queda mucho por hacer con vistas a alcanzar conclusiones menos generales y ambiguas, es decir, más jugosas. Recordemos que los suelos húmedos son mucho más resistentes que los que se encuentran secos, frente a los agentes erosivos eólicos. ¿Podríamos pues inferir que los suelos con horizontes superficies ricos en arcillas son menos resilientes frente la erosión que los que atesoran fracciones gruesas en abundancia?. Con toda franqueza, considero que hacen falta muchas más pruebas como para poder corroborar tal aserto.

Actinobacterias. Fuente: CB TV

Juan José Ibáñez

Lo que el viento se llevo……..

Bacteriodidetes. Fuente: Microbe Wiki

Agricultural Bacteria: Blowing in the Wind

ScienceDaily (May 9, 2012) — It was all too evident during the Dust Bowl what a disastrous impact wind can have on dry, unprotected topsoil. Now a new study has uncovered a less obvious, but still troubling, effect of wind: Not only can it carry away soil particles, but also the beneficial microbes that help build soil, detoxify contaminants, and recycle nutrients.

Using a powerful DNA sequencing technique, called pyrosequencing, a team led by USDA-ARS scientists Terrence Gardner and Veronica Acosta-Martínez analyzed the bacterial diversity in three Michigan agricultural soils, and in two eroded sediments generated from these soils during a wind tunnel experiment: coarse particles and fine dust. Not only were the microbial assemblages on the coarse particles distinct from those on the dust, report the scientists in the current issue of the Journal of Environmental Quality, but the two types of eroded sediments were each enriched in certain groups of microbes compared with the parent soil, as well.

The findings suggest that specific bacteria inhabit specific locations in soil — and thus different groups and species can be carried away depending on the kinds of particles that erode. «It’s important to know which microbes are being lost from soil,» says Acosta-Martínez, a soil microbiologist and biochemist at the USDA-ARS Cropping Systems Laboratory in Lubbock, TX, «because different microbes have different roles in soil processes.»

For example, the Proteobacteria — a diverse group critical to carbon and nitrogen cycling — were more associated in the study with eroded, coarse particles (those larger than 106 microns in size) than with the fine dust. Similarly, the dust housed its own community, in this case Bacteroidetes and other bacteria that are known to tolerate extreme dryness, gamma radiation, and other harsh conditions that may develop on dust particles as they float through the air, says Gardner, a postdoctoral researcher who is also affiliated with Alabama A&M University.

What this means is that wind erosion can both reduce the overall microbial diversity in farm fields, as well as deplete topsoil of specific groups of essential bacteria, say the researchers. At the same time, certain important groups, such as Actinobacteria that promote soil aggregation, remained in the parent soil despite the erosive conditions generated in the wind tunnel. And while fine dust can travel extremely long distances, coarse particles rarely move more than 20 feet, suggesting that they — and their associated microbes — should be fairly easy to retain with cover cropping and other soil conservation measures, Acosta-Martínez notes.

Helping farmers and land managers adopt practices that better conserve soil is one of the main goals of the USDA-ARS team’s work, which also includes Ted Zobeck, Scott Van Pelt, Matt Baddock, and Francisco Calderón. In the Southern High Plains region, for example, intense cultivation of soil combined with a semi-arid climate can result in serious wind erosion problems. In fact, last summer’s drought brought Dust Bowl-like conditions to the area, says Acosta-Martínez.

But «wind erosion is a national problem,» she adds, with significant erosion occurring even in places where the growing season is humid and wet. Organic histosol soils in Michigan and many other parts of the country, for instance, are very susceptible to wind erosion when dry, especially since they’re usually intensively farmed and often left bare in winter. Cover cropping or crop rotations not only help keep these soils in place, but can also build soil organic matter, which in turn promotes soil aggregation, water penetration, and general soil health.

It can take years, however, for farmers who’ve adopted new management practices to detect noticeable changes in levels of soil organic matter and other traditional soil quality measures. This is why Acosta-Martinez and Gardner have been analyzing soils with pyrosequencing, a method that yields a fingerprint of an entire microbial community, and well as identifies specific groups and species of bacteria based on their unique DNA sequences.

In this study, these microbial signatures told the researchers what’s potentially being lost from soil during wind erosion events. But the fingerprints can be early indicators of positive outcomes, too.

«The microbial component is one of the most sensitive signatures of changes in the soil,» says Acosta-Martínez, because of microbes’ involvement in soil processes, such as carbon accumulation and biogeochemical cycling. «So, we’re looking for any shifts in these signatures that could lead us to think that there are benefits to the soil with alternative management.»

Story Source: The above story is reprinted from materials provided by American Society of Agronomy (ASA), via Newswise.

Journal Reference: Terrence Gardner, Veronica Acosta-Martinez, Francisco J. Calderón, Ted M. Zobeck, Matthew Baddock, R. Scott Van Pelt, Zachary Senwo, Scot Dowd, Stephen Cox. Pyrosequencing Reveals Bacteria Carried in Different Wind-Eroded Sediments. Journal of Environment Quality, 2012; 41 (3): 744 DOI: 10.2134

muchas gracias por el post estoy aprendiendo mucho sobre el suelo y su importancia