![]()

On how we retrospectively identified the first case of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Spain

In this post I reproduce a recent article published in The Conversation (in Spanish) in which I described how we came across the first case so far of Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever in Spain, which occurred (now we know) in 2013, three years before the first officially described case up to now. The work was developed in collaboration between my group at the Animal Health Research Center (CISA), at INIA-CSIC, the Majadahonda National Microbiology Center and the Salamanca University Hospital and has been published in the June issue of the prestigious Emerging Infectious Diseases journal. This is an unconventional investigation, which began on Twitter. Hope you like it.

The story I’m about to tell might perhaps surprise you. It is not usual for a conversation on a social network to end up leading to a scientific publication. Even less if this is in one of the most prestigious journals in its area: Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The story involves an emerging disease, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF). This is the description of the first known case of this disease in Spain so far, and we have discovered it thanks to Twitter. Don’t you believe me? Keep reading.

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, caused by a virus (CCHFV) that is transmitted by ticks, produced three cases in Spain last year, all in the province of Salamanca. They were not the first: there were two more in 2018 and another two in 2016 (1).

In April 2020 there was one more case, also admitted to a hospital in Salamanca. It is a very severe disease that causes death in an appreciable percentage of cases. Of the eight cases cited, three died: the first in 2016, another in 2018 and a third in 2020.

The two of 2016 were considered the first cases of this disease in Spain. The first of them was a 62-year-old man, who was presumably infected through a tick bite during a walk in the mountains in southern Ávila (Central Spain). He was admitted to a hospital in Madrid where he died, not before transmitting the virus to a nurse who cared for him, who suffered the disease but, fortunately, managed to overcome it. In 2018 there was a fatal case in Badajoz, related to hunting activities.

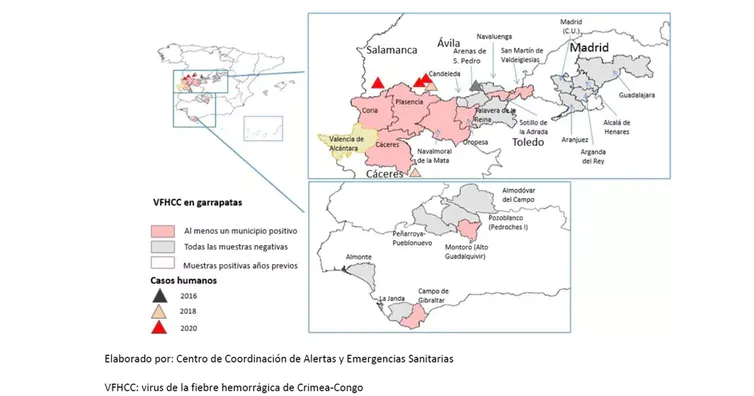

The presence of this virus in Spain is known since 2010. That year, infected ticks were found parasitizing deer on a hunting farm in the province of Cáceres, very close to the border with Portugal. Subsequent studies have located areas of virus circulation in some regions of the Center and South of the Iberian Peninsula, as can be seen in the following map, where the places where human cases occurred are also indicated.

It is worth remembering that this disease, which is endemic in certain areas of sub-Saharan Africa and Central Asia, is expanding in Eastern Europe. Spain is the only country in Western Europe that has declared cases of this disease so far.

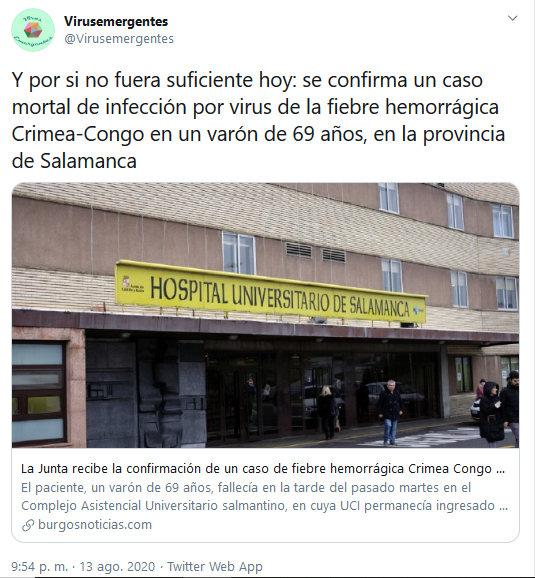

But let’s get back to our story. Last summer a case of this disease was detected in Spain, which had some diffusion in the media, and I commented it on Twitter:

On top of the pandemic coronavirus, and an active West Nile fever outbreak in Andalusia, which so far has been the worst we have suffered in Spain, there was this CCHFV case. Interest in alerts for emerging viruses was on the rise and my tweet became quite popular.

Among the comments/answers received, there was a very special one. One person told me that she had suffered a very serious illness after being bitten by a tick in 2013. He also told me that the bite occurred in the south of Ávila and that she was treated in Salamanca.

She asked me if it was possible to know if Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever had been the cause. Of course, that was very likely, and we could know it. At that very moment I had the feeling that, indeed, it could be a case that would have gone unnoticed. If this were the case, it would be the first case described in Spain, three years before the official debut of this disease in our country.

To investigate this possibility, I contacted the medical team that treated her at the Salamanca University Hospital. There that case had attracted attention due to its severity: a hemorrhagic disease with a possible origin from a tick bite, which left an uncertain diagnosis.

Pathologies caused by infectious agents transmitted by ticks were considered, but at that time no one thought about Crimean-Congo fever. In 2013 it was an unknown disease in Spain except for an important (but barely known) detail that I mentioned before: this pathogen had been detected three years earlier in ticks from a rural area of the province of Cáceres.

I contacted the national reference laboratories of the Carlos III Institute of Health (serology and arboviruses/imported viruses laboratories). There they have been studying evidence for this disease for years and carrying out the reference diagnosis in Spain.

We requested a new blood sample to test for antibodies. The result was unequivocal, by two different techniques: the patient had been infected with CCHFV. We also verified that the antibodies against this disease can remain in the blood for a long time, at least seven years. It was the eureka moment of this story: the first cases so far in Spain dated from 2016. This had happened in 2013!

It became, chronologically, the first case (known so far) of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Spain. The medical reports were very enlightening. The clinical signs were absolutely consistent. Indeed, there was more evidence to come: in 2013 samples had been sent to the Carlos III Institute of Health to analyze the possible infection by pathogens transmitted by ticks (Rickettsia, Ehrlichia, Anaplasma).

Those tests were negative at the time. As we have said, in 2013 the Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus was not even contemplated. These samples now were located and analyzed again, this time to detect CCHFV by PCR and antibodies by serological techniques. Both tests were positive. There was no doubt: it was the first case of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever known in our country.

Will there be other cases that have gone unnoticed?

In addition to anticipating the appearance of the first case in Spain by three years, this study alerts about the possibility that there might be more, even earlier cases that have gone unnoticed. In fact, this is the second case that has been retrospectively diagnosed. There was another in 2018 that was diagnosed in 2019. The first positive ticks were detected in 2010, which could mean that this disease might have been underdiagnosed in our country during these early years.

It is, therefore, the ninth case of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Spain so far*. Of these, three have been fatal (33%). It is a serious threat to public health that, until now, has produced sporadic cases, concentrated in South-Central areas of the country. But that has been until now. How will it evolve? In Turkey they had not even heard of this disease until 2002 when sporadic cases began to occur that were gradually growing until today, which have 1 000 cases per year of which about 50 are fatal.

Hopefully this (still) does not happen in Spain. To avoid this to occur, it is necessary to prepare, establish effective surveillance and promote control of the disease, for which there is no vaccine or specific treatment.

It is also necessary to promote awareness among health workers that this disease is present in our territory so that they must be prepared to detect cases and treat them. In addition, they must know how to protect themselves, as they are at risk of acquiring it when treating affected patients.

This disease requires very strict biocontainment measures to reduce risk for those exposed to the virus. It is a pathogen that requires biocontainment level 4 laboratories to handle it. Spain currently lacks this type of laboratory, so it is difficult to investigate it in our country. It is very important to build such facilities in our country. It is a question of health sovereignty**.

References:

(1) CCAES report RAPID RISK ASSESSMENT – Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever case detection in Salamanca, August 27, 2020 (click here to download the pdf).

NOTES:

*In 2021 two more CCHF cases have been diagnosed in Spain, one in April in Salamanca and the other one in Leon in June.

**A BSL-4 laboratory is going to be built in the Carlos III Institute of Health. The works will be initiated in october 2021 and will be functional by 2025.

ADDITIONAL NOTES:

- This article was based on a thread I posted on Twitter on May 11, coinciding with the publication of the scientific study in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

- More recently, El Confidencial has published an interview with David González Calle (co-author of the article) and myself, about this case and the perspectives that he raises in relation to this disease in our country. Tags: CCHFV, Spain, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Twitter Categories: New viruses