![]()

Suelos Salinos, Aguas Salobres y Agricultura Sustentable

La utilización de suelos salinos con fines agropecuarios es del máximo interés, dada la gran extensión que cubren los suelos naturalmente salinos, así como los salinizados debido a un deficiente sistema de irrigación. El boletín de noticias “Science Centric” publicó en diciembre de 2008 un interesante nota que llevaba por título: “Salt water irrigation: Study shows it works”, basada en un artículo recientemente aparecido en la revista Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. De acuerdo a sus autores resulta posible su explotación utilizando una planta forrajera tolerante a la sal en combinación con otra bioacumuladora de la misma, que tras ser incinerada es convertida en jabón. Tal manejo es acompañado por la irrigación con aguas salobres. La primera especie resulta ser Panicum turgidum, (una especie de gramínea típica de los ambientes desérticos) la segunda no es explicitada, pero hay muchas. Tal actividad puede ser muy interesante con vistas a paliar la producción de alimentos, y en especial en los biomas áridos y semiáridos del planeta, es decir en donde más suele necesitarse.

Panicum turgidum parece ofrecer con tales sistemas de manejo a una producción nada despreciable, que podría aumentar más cuando se ajusten las dosis de fertilizantes adecuadas. Esta planta no absorbe la sal y es rica en proteínas. Sin embargo, al irrigar con aguas salobres, la concentración de sales en un suelo ya de por sí salino, podría aumentar, dañando la fertilidad física (deterioro de la estructura edáfica) y química del suelo, ya se por sí salino. Con vistas a evitar tal problema, los autores proponen pues la inclusión de otra(s) especies que aunque no sean palatables, acumulan las sales es sus tejidos, evitando así que se precipiten en el suelo. Como hemos mencionado, luego de cumplir su misión son recolectadas e incineradas, siendo el producto resultante apto para producir jabón. Al parecer se pueden obtener varias cosechas anuales, lo que ya de por sí añade más valor a este sistema de gestión.

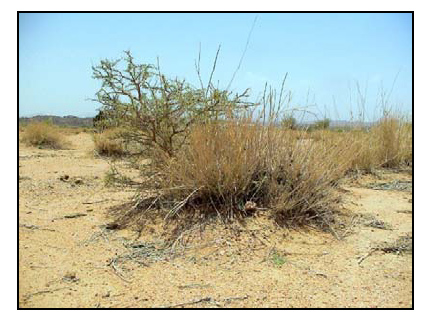

Pastoreo actual en ambientes áridos.

El estudio parece en sí muy interesante, y de resultar cierto podría paliar el hambre en amplias regiones del planeta con una dieta principalmente carnívora, en caso de pueblos autárquicos. Obviamente, también puede entrar en el mercado de exportación para poder adquirir otros alimentos vegetales. Sin embargo, el estudio tan solo cubre un año, por lo que habrá que esperar a analizar como responde el agroecosistema tras varios ciclos anuales. Finalmente, los investigadores no se resisten a poder “tocar los genes” de Pánicum (panicum me producen ellos). Lo que desconozco es en que ambientes y tipos de suelos puede crecer esta especie. Sería raro que fuera viable en casi todos los suelos salinos del mundo irrigados por cualquier clase de aguas salobres. En cualquier caso la publicación parece interesante y habrá que profundizar más en el asunto. Os dejo ya con la noticia en suahili.

Juan José Ibáñez

Salt water irrigation: Study shows it works

Boletín de Noticias “Science Centric”

Take an arid field riddled with salty soil. Irrigate it with salty water. Plant a salt-tolerant grass along with a salt-sucking companion plant and what do you get? If you’re a Brigham Young University research team, you raise a crop that successfully replaces corn as cattle feed.

Their research highlights the promise of using salty water to turn the salty soil in the world’s arid regions into sustainable agricultural land. Just published online in the journal Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment ahead of the February issue, the study identified a plant that could thrive in yet-unusable lands near the coasts in much of the world. But don’t throw away your salt-shakers – the beef from the cattle raised on it tastes just the same as the meat you’re used to.

‘It seems odd that salty soil and salty water could produce useful crops, but that’s what this study showed,’ said Brent Nielsen, chair of BYU’s microbiology and molecular biology department and corresponding author on the study. ‘It’s exciting to share in work that directly benefits people who need to find more land in order to produce the food and income they need to survive.’

The research team focused on a plant called Panicum turgidum that can grow in salty conditions. They measured its protein content and determined that it could be a suitable alternative to existing cattle feed. Then they tested its growth potential when irrigated with the salty water found in the area. They showed that Panicum grew so fast it could be harvested almost monthly. Overall, with limited fertiliser, they produced 60,000 kilograms per hectare during the yearlong study. Nielsen is confident that further studies that determine the best ratios of fertiliser will boost that number over 100,000 kilograms.

The researchers also used nature to preserve a sustainable growing environment. Panicum is a ‘salt excluder,’ meaning it survives salty conditions by keeping salt out of its system, which most other plants can’t do. Although this allows Panicum to grow on salty water, the extra salt deposited by irrigation would render the soil too salty for even this hardy plant. So the researchers found that planting a companion crop that is a ‘salt accumulator’ prevented the soil from getting too salty. The other plant sucked up the extra salt, then was harvested and burned and the ashes turned into soap. After the yearlong study, the levels of salt in the soil were virtually unchanged.

The Balochistan region of southern Pakistan, where Nielsen’s collaborators conducted the test, is one of the world’s driest places, and the underground water supply is ‘brackish’ or salty because of its proximity to the Indian Ocean.

There is a strong demand for fodder to feed the cattle that are a main source of income in the region, so a crop that can grow successfully in these conditions ‘would have enormous impact on the quality of life in local communities,’ said Ajmal Khan, a professor at the University of Karachi, director of the Pakistani research team and first author on the paper.

The Panicum was fed to cattle, and the cattle grew as big or bigger as those fed corn, with similar amounts of protein in their meat. As world populations grow and agricultural land is threatened, this new approach can open up more crops for both livestock and humans, Nielsen said. ‘By being able to transfer production of animal feed closer to the coasts, where you have these salty soils, more useful agricultural lands can be free for vegetable and grain production for human consumption,’ he said.

Now that Nielsen and his research colleagues have established that their approach works, they are taking a closer look at how the plant uses ‘tricks of nature’ to survive a salty environment. Then the researchers want to explore breeding those traits into more traditional food crops. Another possibility is discovering the genes that help it tolerate salt and genetically engineering other plants to do the same. Nielsen’s collaboration with Khan and his other Pakistani colleagues grew out of Khan’s multiple stints at BYU under the guidance of now-retired BYU scientist Darrell Weber. Khan, whose wife Bilquees Gul earned her Ph.D. at BYU and is also a coauthor on the study, said he hopes to ‘continue 23 years of very useful association with BYU.’

Source: Brigham Young University

Buen comentario a la problematica que presentan los suelos salinos a nivel mundial, y si esta graminea es una sulución para pienso del ganado, la inquitud que tengo es como obtener la bendita semilla para poder experimentar en mi medio y sacar mis propias conclusiones. La verdad que este medio actualmente pone a nuestra disposición informacion bastante util. Les agradezco su información y experiencia.

muchas gracias me sirvio un monton las fotos, tienen muy buen programa, los quiero y sobretodo, muchas bendiciones ♥♥♥

DONDE PUEDO COMPRAR SEMILLAS??