![]()

Evolución de la Biodiversidad a lo largo de la Historia de la Tierra

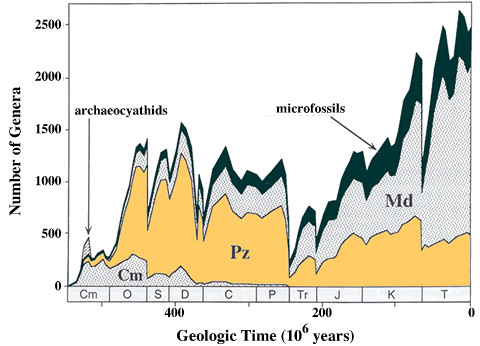

Se ha venido dando por cierto que la biodiversidad ha incrementado desde el origen de La Tierra. En principio, el patrón más aceptado por los científicos fue denominado Curva de Sepkoski El ya fallecido J. John Sepkoski, fue Catedrático de Paleontología de la Universidad de Chicago, y recopiló los datos que dieron nombre al patrón que detectó. Abajo os mostramos su famosa curva. Sin embargo, como podréis observar, recientes investigaciones publicadas en la revista Science y recogidas en dos notas de prensa por Terra Daily en este y también en este enlace ofrecen un cuadro totalmente distinto. Abajo incluimos las dos. Al menos desde hace cientos de millones de años, no parece haber existido incremento de biodiversidad alguno en la faz del planeta, como mínimo en los océanos.

Diversidad de los fondos oceánicos durante el cretácico

No se trata de un descubrimiento intrascendente, ni mucho menos. De ser corroborado nos indicaría que la capacidad de carga de especies de invertebrados en los océanos de La Tierra parece haberse saturado, o al menos estabilizado, desde antes de finales del Cretácico. Hasta la fecha se suponía que la variedad de organismos que yacen en la tierra creció lentamente al principio, para adoptar luego un crecimiento exponencial. Por el contrario, los nuevos resultados corroboran los previamente compilados por Spekoski en lo que concierne a que los trópicos han sido más ricos en especies de invertebrados marinas desde hace 450 millones de años que las latitudes elevadas. Resumiendo, de haber existido un incremento de diversidad a lo largo del Fanerozoico, este ha sido poco significativo.

Curva de Sepkoski Fuente Bulletin of American Paleonlology

Tal hecho no significa que la biodiversidad global no se alterara. Muy por el contrario, la nueva curva detecta más bien una curva ondulante alrededor de un valor medio, con épocas de pérdidas y ganancias. Nadie duda de que se dieran extinciones masivas seguidas por súbitos incrementos del número de especies (radiaciones). Todavía se desconoce si los orígenes de tales cambios fueron causados por eventos catastróficos (impactos de grandes meteoritos, gigantescas erupciones volcánicas, fragmentación y fusión de los continentes) y/o cambios climáticos de gran magnitud y/o por la propia dinámica interna de la biosfera, como sistema complejo. Eso si, los ensamblajes locales en las comunidades locales se asemejan mucho a lo largo de los últimos cientos de millones de años. ¿Ocurrió lo mismo en las masas de tierra emergidas?. No lo sabemos a “ciencia cierta”.

Extinciones causadas por catástrofes naturales

Fuente Nacional Science Fundation

El nuevo estudio parte de mejores bases de datos, potencia computacional, colaboración de numerosos investigadores de varios países etc. Empero el punto clave son los inventarios más completos. De nuevo vuelve a la palestra la necesidad de inventariar adecuadamente los recursos naturales, una actividad denostada, que se traduce en escaso número de publicaciones y el descrédito ante sus colegas de científicos que se han afanado durante años, casi en silencio, en recopilar evidencias. Como ya argumentamos en otro post, la crisis de la taxonomía ha generado que la masa crítica de taxónomos y paleontólogos sí decreciera exponencialmente (en el sentido amplio del término). Tal hecho no se encuentra justificado por criterios lógicos. De seguir así, a medio plazo pocos descubrimientos más de esta guisa podrán salir a la palestra. Nos topamos de nuevo con la irrazonable racionalidad de la ciencia. Más valen 100 papers insustanciales que un buen trabajo de investigación. ¡Falso!.

Huella de un Dinosaurio Jurásico

Species Have Come And Gone At Different Rates Than Previously Believed

by Staff Writers;

Diversity among the ancestors of such marine creatures as clams, sand dollars and lobsters showed only a modest rise beginning 144 million years ago with no clear trend afterwards, according to an international team of researchers. This contradicts previous work showing dramatic increases beginning 248 million years ago and may shed light on future diversity. «Some of the time periods in the past are analogies for what is happening today from global warming,» says Jocelyn Sessa of

J. John Sepkoski

Using contemporary statistical methods and a paleobiology database, the researchers report in the July 4 issue of Science, a new diversity curve that shows that most of the early spread of invertebrates took place well before the Late Cretaceous, and that the net increase through the period since, is proportionately small relative to the 65 million years that elapsed. The research team was led by John Alroy of the

One key to the new curve is the Paleobiology Database, housed at the

The new database allows researchers to standardize sample size because it includes multiple occurrences of each fossil. Researchers can randomly choose equal samples from equal time spans to create their diversity curve. This new curve uses 11 million-year segments, but the researchers hope to reduce the time intervals to 5 million years to match the interval of the previous curve, known as Sepkoski. The data for this study contains 284,816 fossil occurrences of 18,702 genera that equals about 3.4 million specimens from 5384 literature sources. The old curve, developed by J. John Sepkoski Jr., used a database that contained only about 60,000 occurrences.

The researchers also looked at evenness in diversity. If there are 100 specimens divided into 10 time intervals, they could be divided with 10 individual specimens in each interval, or 91 specimens could be in one interval with one each in the remainder. The more even the distribution, the higher the evenness.

«Evenness says something about resource distribution,» says Patzkowsky. «Much of invertebrate diversity has been attributed to diversity increase in the tropics, but the curve is not driven by that totally. It seems that 450 million years ago was not so different from today because it also contained more diversity in the tropics. «The major points of the Sepkoski curve are still seen in the new curve. Some things that are not seen, such as the decrease in diversity due to the Cretaceous Tertiary (KT) extinction 65 million years ago are not visible because of the scale of the intervals used. The extinction and recovery in the KT took less than 11 million years and so do not show.

Some things not seen on the Sepkoski curve include a peak in the Permian. Also unexpected is that the diversity in the Jurassic (206 to 144 million years ago) is lower than diversity in the Triassic (248 to 206 million years ago), indicating a dip and rise in the diversity curve. The curve then rises in the Cretaceous and remains more or less flat after that. The previously thought exponential increase in diversity is not there.

«Comparing diversity through time is about how our world works, about the origin of species and how diversity changes with temperature,» says Sessa. «If we think that the net increase over time will not get much greater, things are very different from if the diversity increases exponentially.»

Species Diversity Less Dramatic Than Believed

by Misha Kidambi;

The analysis helped the researchers conclude that the increase in species diversity through the Phanerozoic Era was much less dramatic than previously believed.

A study published in the current issue of Science challenges the long-held belief that diversity of marine species has been increasing continuously since the origin of animals. Dr. Thomas D. Olszewski, a geology and geophysics professor at Texas A and M University, has been a part of the international team that carried out this decade-long study, which concludes that most of the diversification occurred early on – relatively speaking.

«The general understanding for many decades has been that since the rise of the modern major groups of animals about 545 million years ago (i.e., since the beginning of the Phanerozoic Era), the diversity of animal life in the seas has undergone a roughly four-fold exponential increase,» says Olszewski. A steep increase in the diversity was believed to have occurred only between 145 million and 60 million years ago. But many paleontologists were doubtful about the accuracy of this theory, which was derived using older methods.

Olszewski explains that the older methods did not account for many important occurrences in the history of the Earth, including changes in the geography of Earth due to continental drift and variations in the state of global climate. Collaborative efforts of 35 researchers from the

The analysis helped the researchers conclude that the increase in species diversity through the Phanerozoic Era was much less dramatic than previously believed. «Diversity levels comparable to the present day appear to have been reached after a few tens of millions of years following the first appearance of modern animal groups,» says Olszewski. The new fossil data also indicate that the current pattern of distribution of life – with low species diversity in the poles and a very high diversity in the tropics – was established some 450 million years ago. With the huge amount of data that was used for the analysis, (fossil occurrences representing nearly 3.5 million specimens) it also became possible to assess the diversity changes in local ecological communities as well as in that of the global total.

Again, the researchers concluded that local ecological communities have changed relatively little since the establishment of marine animal ecosystems during the Phanerozoic Era. So what bearing do the study conclusions have on the life on Earth today? Maybe a great deal, Olszewski says. «As global climatic conditions change, either naturally or anthropogenically, (animal) life responds, which in turn can influence human life,» says Olszewski. «Understanding what life was like under different conditions can help us assess and prepare for the consequences of this ongoing change,» he adds.

Una mala noticia para mi teoría particular…

En cualquier caso, es lógica una tendencia al aumento de la biodiversidad sobre la Tierra a grandes rasgos, pues antes de la evolución de las eucariotas no pudo haber biodiversidad de las mismas, antes de los pluricelulares no pudo haber biodiversidad de insectos, etc.

Es posible que exista un techo de biodiversidad, y además esa posible tendencia de aproximarse la Tierra a él, se ve oscurecida por los episodios de Gran Extinción y seguramente por el ciclo Pángea (cuando se dividen los continentes aumentará la biodiversidad, cuando se juntan los continentes ¿habrá pérdida de biodiversidad?

Un abrazo y gracias por la información,

Carlos de Castro

Carlos tampoco estaba entre mis suposiciones plausibles. Es posible que se alcanzara un techo pronto. Efectivamente es lógico pensar que la fragmentación y fusión de los continentes "Ciclo de Wilson" que me gusta visualizarlo como el latido de la Tierra marca el ritmo de las extinciones y radiaciones a muy largo plazo. Obviamente hay otros de menor duración. Cuando colisionaron las Américas, al cerrarse el Itsmo de Panamá se produnjo una gran extinción de especies (segun dicen llos expertos),

Saludos

Juanjo Ibáñez

[…] Evolución de la Biodiversidad a lo largo de la Historia de la Tierra […]

ami me ayudo mucho este articulo para mi tarea de ciencias^^

hola. NO me sirvió esto para la escuela

NO ME SIRVIÓ. GRACIAS IGUAL…

[…] Evolución de la Biodiversidad a lo largo de la Historia de la Tierra […]

Very good article, if u are interested in article like this u can visit my page https://telkomuniversity.ac.id/