![]()

La biomasa microbiana y su importancia en los suelos

La nota de prensa que os ofrecemos hoy nos informa de la importancia de la materia orgánica de origen bacteriano en los suelos. así como de su papel en la estructura de los ecosistemas edáficos, fertilidad y secuestro de carbono atmosférico. Se trata de nuevas indagaciones que, en parte, cambian la percepción vigente, del rol desempeñado por las sustancias húmicas en los suelos. Toda novedad debe ser corroborada debidamente antes de incorporarse al corpus doctrinal de una disciplina, por lo que habrá que esperar estudios posteriores con vistas a validar si se trata de “ciencia buena”. Hasta la fecha los expertos sostenían que la mayor parte de la materia orgánica (SOM) de los suelos era de origen vegetal, con independencia del papel que finalmente pudieran desempeñar otras fuentes. Sin embargo, lo que dice haber descubierto este esquipo de investigadores alemanes cuestiona tal tesis. De acuerdo con ellos la biomasa bacteriana y en especial la procedente de sus paredes celulares desempeña un rol esencial, acumulándose en cantidades considerables, por lo que resultaría ser esencial no solo en la formación de los agregados del suelo, sino en el almacenamiento de carbono (y como corolario en su secuestro de la atmosférico, a largo plazo (…).

Descomposición de la materia orgánica del suelo. Fuente: Maximum Yield

De acuerdo a estos investigadores, buena parte de los restos vegetales (los más fáciles de metabolizar) serían asimilados por las comunidades microbianas del suelo pasando a formar parte de su biomasa. Más aun un 40% de la última se transformaría en sustancias húmicas resistentes a la mineralización. Al morir, fragmentos nanométricos de estas paredes bacterianas se acumulan en el medio edáfico. En tal proceso parecen intervenir “de alguna manera” los péptidos y proteínas del citoplasma celular, que de este modo persisten en mayor medida en el suelo que otros componentes del microrganismo. Estos materiales permiten la formación de películas moleculares orgánicas que cementan y estabilizan los componentes minerales del suelo, pero también a ellas mismas (resistencia a la mineralización).

Cuando los fragmentos de estas paredes celulares bacterianas se secan, pueden perder sus propiedades de goma cementante, endureciéndose como el vidrio. Si con posterioridad el suelo se humedece de nuevo, tales fragmentos de SOM microbiano no pueden humectarse simultáneamente, requisito previo para su mineralización por el ataque de otras bacterias. Tal mecanismo ofrecería una explicación más simple que las actuales hipótesis a la hora de dar cuenta de la estabilización de compuestos de carbono que, en teoría, deberían ser fácilmente degradables.

Al margen de análisis de laboratorio (microscopios electrónicos de barrido isótopos de carbono estable, etc.,), estos bioquímicos alemanes usan como campo de pruebas la formación del suelo y sucesión natural de la vegetación (de musgos y líquenes a herbáceas, de estas a matorrales, hasta que finalmente crece el arbolado) de un antiguo glaciar que se desheló hace unos 150 años. Y al hacerlo constataron que la cantidad de SOM bacteriano que rodea las partículas minerales incrementa sosteniblemente con el tiempo. Por lo tanto, una buena parte los restos vegetales se transforman con relativa rapidez en biomasa microbiana que da lugar a un incremento de fertilidad física (estructura del suelo), que a su vez retroalimenta el crecimiento microbiano y como corolario la acumulación de las mentadas nanopartículas de paredes bacterianas.

En la nota de prensa no parece quedar muy claro (aunque hacia el final del texto se insinúa algo) si todo este proceso tan solo afecta a las bacterias o también implica a otros microrganismos del suelo cuya abundancia nadie cuestiona como hongos, actinomicetos, levaduras y arqueas.

Los autores, dejando de ser originales, terminan su desiderata realzando la importancia de todo este proceso en el secuestro de carbono atmosférico, punto en el cual comencé a echarme una siesta sobre la consola de mi PC.

Pues bien, parte de toda esta narración ya era conocida y en especial el rol de del SOM de los microrganismos en la formación y estabilización de agregados. “Debo suponer” que muchos detalles y las cantidades narradas sí son primicia científica, aunque como mi bioquímica del suelo se encuentra obsoleta (……)

Juan José Ibáñez

Fertile Soil Doesn’t Fall from the Sky: Contribution of Bacterial Remnants to Soil Fertility Has Been Underestimated Until Now

Sciencedaily Dec. 14, 2012 — Remains of dead bacteria have far greater meaning for soils than previously assumed. Around 40 per cent of the microbial biomass is converted to organic soil components, write researchers from the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ), the Technische Universität Dresden (Technical University of Dresden) , the University of Stockholm, the Max-Planck-Institut für Entwicklungsbiologie (Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology) and the Leibniz-Universität Hannover (Leibniz University Hannover) in the journal Biogeochemistry.

Until now, it was assumed that the organic components of the soil were composed mostly of decomposed plant material which is directly converted to humic substances. In a laboratory experiment and in field testing the researchers have now refuted this thesis. Evidently the easily biologically degradable plant material is initially converted to microbial biomass which then provides the source material to soil organic matter.

Soil organic matter represents the largest fraction of terrestrially bound carbon in the biosphere. The compounds therefore play an important role not only for soil fertility and agricultural yields. They are also one of the key factors controlling the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Climatic change can therefore be slowed down or accelerated, according to the management of the soil resource.

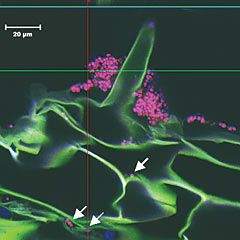

In laboratory incubation experiment, the researchers initially labelled model bacteria with the stable isotope 13C and introduced the bacteria to soil deriving from the long-term cultivation experiment «Ewiger Roggenbau» in Halle/Saale. Following the incubation time of 224 days the fate of the carbon of bacterial origin was determined. «As a result we found fragments of bacterial cell walls in sizes of up to 500 x 500 nanometres throughout our soil samples. Such fragments have also been observed in other studies, but have never been identified or quantified,» declares Professor Matthias Kästner of the UFZ. The accumulation of the bacterial cell wall fragments appears to be supported by peptides and proteins from the liquid interior of the cells, which remain to a greater extent in the soil than other cell components. These materials enable the formation of a film of organic molecules on the mineral components of the soil, on which the carbon from the dead bacteria is accumulated and stabilised.

When the fragments of the bacterial cell walls dry out, they may lose their rubber-like properties and can harden like glass. If the soil subsequently becomes moist again, however, under certain circumstances they cannot be re-wetted — an important prerequisite for their degradation by other bacteria. This would provide the simplest explanation for the stabilisation of theoretically easily degradable carbon compounds in soil. «This new approach explains many properties of organic soil components which were previously viewed as contradictory,» says Matthias Kästner. In the late 1990s, Kästner and his team arrived at this idea on the basis of earlier investigations on the degradation of environmental contaminants like anthracene in polluted soils of former gas work sites. In these investigations, isotopic analyses revealed bound carbon residues which have been of bacterial origin. With the support of the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft; DFG), from 2000 on they began to follow up this clue within the scope of two joint research programmes.

Following the laboratory experiment, the hypothesis was tested in field research. In summer of 2009 the researchers took soil samples in the forefield of the Damma Glacier in the Swiss Canton Uri. In the course of the last 150 years glacier has retreated by around one kilometre. In its place granite rock remained behind, which was gradually recolonised by living organisms accompanied by soil development. Following the formation of new soil the first plants, such as mosses and grasses, were followed by bushes and, later, also by trees. In the meantime, the Damma Glacier, on which a broad range of studies is being conducted, has therefore become an important outdoor laboratory not only for climate researchers, but for ecologists as well. The soil investigated with the samples was between 0 and 120 years old and thus allowed insight into early processes of soil development. Scanning electron microscopic investigations which followed at the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tübingen also indicated that the covering of the soil mineral particles by a film composed of bacterial cell wall residues had increased with the soil age. The results of the outdoor investigations therefore confirmed the hypothesis and the laboratory results. This new knowledge was ultimately made possible by recent advances in scanning electron microscopy, which in the meantime enable the identification and evaluation of the soil nano-components.

The predominant share of the plant debris in fertile soil is thus rapidly processed by micro-organisms, e.g. bacteria, leading to more bacteria and, in turn, also to more cell fragments. This then results in more organic material in the soil. «Even though the greatest part of the organic carbon in the eco-systems is definitively produced primarily by plants, we were able to show that a large part of the organic material is actually composed of residues of bacteria and fungi. This underscores the importance of bacteria as organisms in all types of soil,» summarises Matthias Kästner. Furthermore, they are important for the global climate: The degradation of these organic material results, in mineralisation products and the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO2). According to estimates from Great Britain the amount of CO2 escaping annually to the atmosphere due to the degradation of organic material in the soils of England and Wales is in the order of magnitude by which greenhouse gas emissions are annually reduced there. This means that no rigorous progress in climate protection may be accomplished without first protecting the soil.

Story Source: The above story is reprinted from materials provided by Helmholtz Centre For Environmental Research – UFZ. Note: Materials may be edited for content and length. For further information, please contact the source cited above.

Journal References: (1) Christian Schurig, Rienk H. Smittenberg, Juergen Berger, Fabio Kraft, Susanne K. Woche, Marc-O. Goebel, Hermann J. Heipieper, Anja Miltner, Matthias Kaestner. Microbial cell-envelope fragments and the formation of soil organic matter: a case study from a glacier forefield. Biogeochemistry, 2012; DOI: 10.1007/s10533-012-9791-3; Anja Miltner, Petra Bombach, Burkhard Schmidt-Brücken, Matthias Kästner. SOM genesis: microbial biomass as a significant source. Biogeochemistry, 2011; DOI: 10.1007/s10533-011-9658-z

buenas soy tesista del INIFAP y estoy realizando una tesis sobre la importancia de los microorganismos me interesa su publicacion podria pasarme completa a mi correo por favor. saludos.

Luis Enrique,

Si trabajas ya en el tema debes aprender como y a quien pedir la bibliografía. Se busca a uno de los autores (generalmente ene la propia revista o en el centro donde trabaja uno encuentra la dirección de mail, luego se le escribe a el y se le solicita. Esa es la forma ortodoxa. Yo he tardado 15 segundos en hacerlo, por lo que debes practicar tu para aprenderlo. Mira aquí.

https://www.ufz.de/index.php?en=4459&sid=8609229745&action=print&print=1

Si quieres investigar debes ir aprendiendo todo esto.

saludos Juanjo Ibáñez