![]()

El Fracaso del Libre Comercio y la Contrarrevolución Agraria Africana

Cualquiera que tenga dos dedos de frente, y atesore un poco de objetividad, no podrá negar la falacia de los valedores de la globalización económica, cuando defienden que la economía del libre comercio es capaz de autoregularse. Más bien nos encontramos sufriendo los efectos opuestos: un descontrol atroz que favorece a los más ricos, fomenta la corrupción y genera hambre en el mundo. África es el caso más paradigmático, a la par que dramático. Un estudio recientemente publicado por el PNAs constata lo evidente. El libre mercado y la prometida revolución tecnológica de la agricultura, basada en una biotecnología servil a los intereses de la agroindustria, subsumen a los ciudadanos de los países pobres en la más absoluta miseria, como la noticia que ofrecemos en este post expone con toda crudeza, claridad y contundencia. África, pasa hoy más hambre que nunca. Sus paupérrimas infraestructuras (falta de carreteras, alejamiento de los mercados, agua potable), carencia de formación del campesinado con vistas a absorber, incorporar y manejar las nuevas tecnologías, y las habituales corrupciones gubernamentales, hacen volver la vista hacia las décadas precedentes, en donde la agricultura tradicional y los mercados locales, al menos permitían que las hambrunas fueran menos frecuentes e intensas. De hecho, los Estados y regiones que las han mantenido padecen actualmente menos desastres humanitarios, según nos informan los expertos.

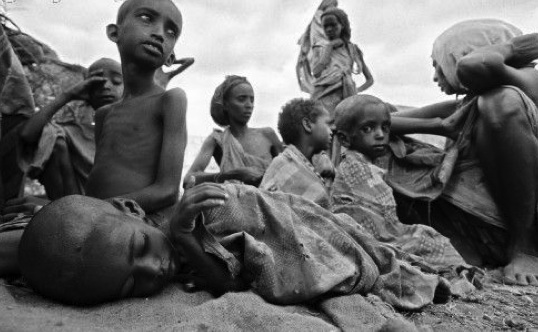

Las miserias del capitalismo en África. Fuente: Caputo children’s fund

La denominada crisis alimentaria de 2008 tan solo fue el detonante de una bomba de relojería que iba a estallar tarde o temprano. Hace unos días, leía que a principios de la década de 1990, tan solo España comenzó a superar el PIB de todo el continente africano. ¡Increíble!, pero al parecer cierto. Imagínense producir para vender en mercados a cientos o miles de kilómetros de distancia, sin carreteras, sin coches, sobre suelos generalmente pobres y sin a penas fertilización, sin contar con una crónica escasez (por lo general) de recursos hídricos.

Parece ser que casi todos los occidentales olvidamos que las tenencias de las tierras de los pueblos indígenas, carecen en la mayoría de los casos de legalidad para sus gobernantes. No suele haber papeles que atestigüen la propiedad en manos de sus legítimos propietarios. Por estas razones, no es infrecuente que, aquí y en Latinoamérica, los gobiernos sin escrúpulos expulsen a los pobres campesinos de sus terrazgos para otorgárselos a terratenientes y/o multinacionales. El desamparo de la población es total. La pobreza generada en África tras intentar incorporarla al libre mercado ha devenido en un éxodo de los más desheredados a las inseguras urbes, hacinándose en condiciones infrahumanas e insalubres.

En otros casos, los corruptos gobernantes venden o permiten explotar las tierras a multinacionales para que exploten sus recursos naturales (petróleo, recursos minerales y ahora materia para agrocombustibles) forzando la expulsión de sus moradores hacia un destierro incierto y desconocido en pro de la acumulación del dinero, así obtenido, por golfos y sinvergüenzas, cuando no ostentadores del doloso cargo de magnicidio.

Los científicos firmantes de la publicación en el PNAS (ver abajo el resumen), ponen el dedo en la llaga al señalar que en realidad “no hay un libre mercado real en nuestra economía”. Yo diría más, se trata de mera rapiña institucionalizada. En consecuencia, plantean que una de las soluciones deviene en retornar a las agriculturas y mercados tradicionales, desglobalizando parte de los territorios afectados. Deberemos retornar sobre este tema, por cuanto, se trata de una solución económica, pero también humana y ambiental. Pero no nos engañemos las “reservas” al estilo latinoamericano son una mera perversión de la propuesta que ya esbozaremos.

Sin embargo, de nada de esto hablan los colegas biotecnólogos ¿verdad?. Es muy fácil sentar cátedra desde el laboratorio, ajeno a lo que ocurre en el mundo. Pero de nada de esto nos informan los defensores de los biocombustibles, que con su expansión por el tercer mundo han sido responsables de más destierros, hambrunas, impacto ambiental y pérdida de biodiversidad. Pero de nada de esto dicen ….. y uno podría seguir ad nauseam.

Juan José Ibáñez

Free Trade Loss of Support Systems Crippling Food Production in Africa

ScienceDaily (Feb. 16, 2010) — Despite good intentions, the push to privatize government functions and insistence upon «free trade» that is too often unfair has caused declining food production, increased poverty and a hunger crisis for millions of people in many African nations, researchers conclude in a new study.

Market reforms that began in the mid-1980s and were supposed to aid economic growth have actually backfired in some of the poorest nations in the world, and just in recent years led to multiple food riots, scientists report Feb 15 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

«Many of these reforms were designed to make countries more efficient, and seen as a solution to failing schools, hospitals and other infrastructure,» said Laurence Becker, an associate professor of geosciences at Oregon State University. «But they sometimes eliminated critical support systems for poor farmers who had no car, no land security, made $1 a day and had their life savings of $600 hidden under a mattress.

«These people were then asked to compete with some of the most efficient agricultural systems in the world, and they simply couldn’t do it,» Becker said. «With tariff barriers removed, less expensive imported food flooded into countries, some of which at one point were nearly self-sufficient in agriculture. Many people quit farming and abandoned systems that had worked in their cultures for centuries.»

These forces have undercut food production for 25 years, the researchers concluded. They came to a head in early 2008 when the price of rice — a staple in several African nations — doubled in one year for consumers who spent much of their income solely on food. Food riots, political and economic disruption ensued.

The study was done by researchers from OSU, the University of California at Los Angeles and Macalester College. It was based on household and market surveys and national production data.

There are no simple or obvious solutions, Becker said, but developed nations and organizations such as the World Bank or International Monetary Fund need to better recognize that approaches which can be effective in more advanced economies don’t readily translate to less developed nations.

«We don’t suggest that all local producers, such as small farmers, live in some false economy that’s cut off from the rest of the world,» Becker said.

«But at the same time, we have to understand these are often people with little formal education, no extension systems or bank accounts, often no cars or roads,» he said. «They can farm land and provide both food and jobs in their countries, but sometimes they need a little help, in forms that will work for them. Some good seeds, good advice, a little fertilizer, a local market for their products.»

Many people in African nations, Becker said, farm local land communally, as they have been doing for generations, without title to it or expensive equipment — and have developed systems that may not be advanced, but are functional. They are often not prepared to compete with multinational corporations or sophisticated trade systems. The loss of local agricultural production puts them at the mercy of sudden spikes in food costs around the world. And some of the farmers they compete with in the U.S., East Asia and other nations receive crop supports or subsidies of various types, while they are told they must embrace completely free trade with no assistance.

«A truly free market does not exist in this world,» Becker said. «We don’t have one, but we tell hungry people in Africa that they are supposed to.»

This research examined problems in Gambia and Cote d’Ivoire in Western Africa, where problems of this nature have been severe in recent years. It also looked at conditions in Mali, which by contrast has been better able to sustain local food production — because of better roads, a location that makes imported rice more expensive, a cultural commitment to local products and other factors.

Historically corrupt governments continue to be a problem, the researchers said. «In many African nations people think of the government as looters, not as helpers or protectors of rights,» Becker said. «But despite that, we have to achieve a better balance in governments providing some minimal supports to help local agriculture survive.»

An emphasis that began in the 1980s on wider responsibilities for the private sector, the report said, worked to an extent so long as prices for food imports, especially rice, remained cheap. But it steadily caused higher unemployment and an erosion in local food production, which in 2007-08 exploded in a global food crisis, street riots and violence. The sophisticated techniques and cash-crop emphasis of the «Green Revolution» may have caused more harm than help in many locations, the study concluded.

Another issue, they said, was an «urban bias» in government assistance programs, where the few support systems in place were far more oriented to the needs of city dwellers than their rural counterparts.

Potential solutions, the researchers concluded, include more diversity of local crops, appropriate tariff barriers to give local producers a reasonable chance, subsidies where appropriate, and the credit systems, road networks, and local mills necessary to process local crops and get them to local markets.

Story Source: Adapted from materials provided by Oregon State University, via EurekAlert!.

Juanjo imaginate nuestra impotencia y tener que soportar las barbaridades de nuestro presidentito, pregonando el antiproteccionismo, permitiendo las siembras de transgenicos y dejando morir de inanición la investigación y sobre todo la agrícola.

Hola Régulo,

De una manera u otra, dependiendo de las circunstancias geopolíticas, todos estamos pagando la estulticia de la globalización. Claro está que unos casos son muchísimo más sangrantes que otros.

Un abrazo

Juanjo Ibáñez