![]()

Todo lo que no sabemos del Biochar y ni tan siquiera nos hemos planteado (Una conjetura acerca de su origen y función)

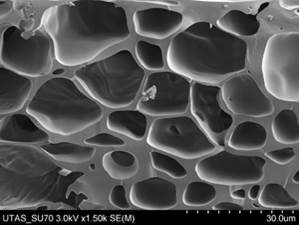

En un capítulo anterior…. (como se dice en las series televisivas) comentamos con sarcasmo varios aspectos de la noticia de prensa sobre la que hoy retornamos nuevamente, ya que aporta otros aspectos que sí atesoran bastante interés. Así por ejemplo, se comenta que el biochar producido a mayores temperaturas posee mejores propiedades con vistas a retener agua y nutrientes que los que fueron fabricados a temperaturas inferiores. De aquí se infiere un aspecto que suele omitirse de una buena parte de la literatura científica sobre este tema. Como podréis documentaros a partir de los post previos (ver relación al final de este) que hemos escrito acerca de las propiedades de los suelos con horizontes orgánicos antrópicos conocidos en Brasil como Terra Preta do indio. Su materia orgánica podía permanecer sin descomponerse a lo largo de varios milenios, aspecto que dista mucho de haber sido demostrado con los productos industriales que actualmente se venden como herederos de aquellos. Del mismo modo, se señala implícitamente que se desconoce cómo obtener la enmienda/corrector/ estructurador que llegaron a desarrollar con enorme éxito los pueblos indígenas del Amazonía. Por otro, lado los investigadores que llevaron a cabo el estudio, mentan que añadieron biochar y nutrientes, no solo el primero. Es decir que el biochar requiere que se enriquezca adicionalmente con una fuente de nutrientes que, bien pudiera ser materia orgánica sin tratar (es decir fresca), residuos fecales o enmiendas minerales. Debo suponer que los indígenas hicieron uso de la primera o segunda, por cuanto las fuentes locales de nutrientes minerales resultan ser muy escasas en la región. Ahora bien, cabe preguntarse de que tipo de producto y tratamiento hablamos. Por un lado las empresas que comercializan hoy el denominado biochar lo hacen exclusivamente utilizando como materia prima hojas y/o trozos de madera, en general. Y así se puede leer en la literatura y marketing empresarial hablar del biochar en base a sustratos del haya, roble, álamos, etc. Sin embargo, seguimos desconociendo totalmente los procedimientos indígenas. No resulta descabellado pensar que bien pudieran añadir, sustancias, compuestos o materiales específicos que favorecieran la producción de un biochar concreto o que actuaran como productos catalíticos de las reacciones generadas de “alguna forma”. En otras palabras, actualmente se vende algo bastante puro, mientras que no es descabellado conjeturar que las culturas aborígenes combinaran materiales diversos, en cantidades concretas, a modo de coctel. Quizás por esa razón los indígenas consiguieran una enmienda cuyas propiedades la tecnología moderna no ha logrado emular. Pero una vez vista la estructura enormemente porosa del biochar indígena, también cabe preguntarse (…)

(….) qué tipo de papel jugaba en el seno las culturas de aquellos pueblos. Me explico. Como podréis observar, al principio del post (y también en alguno anterior) me he referido al biochar como enmienda/corrector/estructurador. ¿Por qué?. Sospecho que pueden equivocarse quien piense que se trata de añadir la sustancia al medio edáfico sin más. Empero un producto puede aplicarse como abono, en el sentido que al entrar en contacto con el medio edáfico, al disolverse/ descomponerse/mineralizarse, desprenda nutrientes, o simplemente que fuera un corrector de la estructura original de los suelos naturales de la región. En este sentido cabe recordar que los Ultisoles y Oxisoles (Acrisoles y Ferralsoles), dominantes en la Cuenca del Amazonas, atesoran unas pobres propiedades químicas y físicas. Las primeras obedecen a la pobreza en nutrientes, mientras la segundas son inducidas por atesorar mayoritariamente arcillas que, como las de tipo caolinítico, retienen mucho peor los nutrientes que otras como lo son las de naturaleza montnorillonítica, en el sentido más amplio del vocablo (es decir “expandibles” o “reactivas”) que los fijan muy bien y en gran cantidad. Empero estas últimas no suelen presentarse en suelos viejos y evolucionados como los aludidos de la Amazonía.

En consecuencia, podría conjeturarse que el biochar indígena bien pudiera ser un horizonte orgánico artificial, sobreimpuesto al natural, con vistas a que aquellos suelos retuvieran bien los nutrientes. Y así, las enmiendas orgánicas naturales (es decir, sin tratar) se añadirían después a modo de genuinas enmiendas. Por tanto, el biochar podría conceptualizarse como un estructurador (mejorador de las propiedades físicas) de aquellos pobres horizontes orgánico-minerales, dando cuenta el abono de un enriquecimiento de las propiedades químicas. El hecho plausible de añadir restos orgánicos frescos sobre el aquel biochar ancestral podría ser la causa de que, al mezclarse, nos impida visionar la estructura de aquél horizonte artificial. Hablaríamos pues de verdaderos tecnosuelos, por mucho que no tengan cabida actualmente en los grupos de suelos de referencia de la WRB. Obviamente, se trata de una mera conjetura, aunque me parece digna de ser sopesada.

Espero haber añadido un granito de fertilidad al tema, aunque no puede descartarse que sea una fantasía del impresentable administrador de esta bitácora. En cualquier caso, reiteramos que los biochar comerciales parecen no tener las excepcionales y casi inauditas propiedades que los científicos otorgan al producto indígena en la literatura científica. Os vuelvo pues a dejar la nota de prensa que ha dado lugar a estos dos post, tan dispares entre sí.

Juan José Ibáñez

Biochar quiets microbes, including some plant pathogens

by Staff Writers. Houston TX (SPX) Oct 03, 2013

In the first study of its kind, Rice University scientists have used synthetic biology to study how a popular soil amendment called «biochar» can interfere with the chemical signals that some microbes use to communicate. The class of compounds studied includes those used by some plant pathogens to coordinate their attacks.

Biochar is charcoal that is produced – typically from waste wood, manure or leaves – for use as a soil additive. Studies have found biochar can improve both the nutrient- and water-holding properties of soil, but its popularity in recent years also owes to its ability to reduce greenhouse gases by storing carbon in soil, in some cases for many centuries.

The new study, published online this month in the journal Environmental Science and Technology, is the first to examine how biochar affects the chemical signaling that’s routinely used by soil microorganisms that interact with plants.

«A potted plant may look tranquil, but there are actually a lot of conversations going on in that pot,» said study co-author Joff Silberg, associate professor of biochemistry and cell biology and of bioengineering at Rice. «In fact, there are so many different conversations going on in soil that it was impractical for us to determine exactly how biochar was affecting just one of them.»

So Silberg and colleagues used the tools of synthetic biology – and a refined experimental setup that Silberg initially drafted with his son’s spare Lego bricks – to establish a situation where just one microbial conversation was taking place and where biochar’s effects on that conversation could be measured.

The study is the latest from Rice’s interdisciplinary Biochar Research Group, which formed in the wake of Hurricane Ike in 2008 when the city of Houston called for ideas about how to get rid of the estimated 5.6 million cubic yards of fallen trees, broken branches and dead greenery left behind by the storm.

The Rice Biochar Group won the $10,000 grand prize in the city’s «Recycle Ike» contest and used the money to jump-start a wide-ranging research program that has since received support from the National Science Foundation, the Department of Energy, Rice’s Faculty Initiative Fund, Rice’s Shell Center for Sustainability and Rice’s Institute of Bioscience and Bioengineering.

The cell-signaling study grew out of a previous investigation by one of the group’s founding members, Carrie Masiello, associate professor of Earth science. Masiello and another member of the group, Rice biologist Jennifer Rudgers (now at the University of New Mexico), were investigating the combined effects of adding biochar and nutrients to soils.

In all but one case, the biochar and nutrients seemed to enhance one another. In the lone exception, a soil fungus that was typically beneficial to plants began growing so rapidly that it impeded plant growth.

«All of these organisms, to a much greater extent than we probably understand, are talking to each other all the time,» Silberg said.

«Microbes talk to microbes. Microbes talk to plants. Plants talk to microbes. And they each make decisions about their behavior based on those conversations. When we started talking about these results, my first thought was, ‘You’re probably interfering with a conversation.'»

There was no practical way to isolate the conversation that was likely being interfered with in the previous experiment, but Silberg thought of a way to create engineered microbes to test the idea of whether biochar could interfere with such a conversation.

His lab began by working with Matt Bennett, assistant professor of biochemistry and cell biology at Rice, to make use of two tailored forms of E. coli bacteria created by Rice graduate student Chen Ye. One strain «spoke» with a type of chemical communication commonly used by soil microbes, and the other «listened.»

Unlike the fungi that use this communication method in soil, the E. coli could be grown in clear agar gels in a petri dish, which meant the researchers could more easily observe them under a microscope. The team next inserted florescence genes into each organism, which caused them to glow different colors – red for speaking and green for listening.

«We needed a way to conduct two experiments in the same dish, one where biochar had a chance to interfere with a conversation and another where it didn’t,» Silberg said.

Working with his son’s Legos, Silberg constructed a pair of rectangular platforms that sat parallel in the dish, about one inch apart. Agar was added to fill all parts of the dish except for the areas blocked by the bricks. Once the agar gel had set, the rectangular platforms were removed to create two empty parallel troughs.

One of these was filled with clear agar, and the other was filled with agar containing biochar. «Speaker» organisms were added to the middle of the dish, and «listeners» were placed on the opposite side of each trough.

Graduate student Shelly Hsiao-Ying Cheng refined Silberg’s Lego design and used tools at Rice’s Oshman Engineering Design Kitchen to create a set of sturdy platforms for repeated tests. The group then ran dozens of microscopy tests with Dan Wagner, Rice associate professor of biochemistry and cell biology, to see how different formulations and amounts of biochar affected cell signaling.

Algunos comentarios adicionales extraídos de la Página Web de la Universidad de Rice.

(….) In every case, we observed significantly less green light from the opposite side of the biochar, which meant the E. coli on that side had trouble hearing the sender,” Silberg said. “That upheld our hypothesis, which was that biochar could interfere with cell signaling, most likely by binding with the fatty-acid molecules that the speakers were using to broadcast their message.”

The team found that biochar that was created with higher temperatures was as much as 10 times more effective at shutting down conversations. The researchers said this finding was significant because it jibed with the results from a 2012 study by Masiello that found that biochars created with higher-temperature processes were more effective at holding water and nutrients.

“Biochar can be made in processes that range from 250 to 1,000 degrees Celsius, and there’s mounting evidence that the temperature can dramatically affect the final properties,” Masiello said. “Ultimately, we’d like to create a simple guide that people can use to tailor the properties of their biochar.”

Silberg added, “Some microbes help plants and others are harmful. That means there’s good communication and bad communication going on in the soil at the same time. We think it’s likely that some biochars will knock out some conversations and not others, so we want to test that idea and, if possible, come up with a way to tailor biochar for the microbial diversity that’s desired.”

Study co-authors include Ye Chen, Xiaodong Gao, Shirley Liu and Kyriacos Zygourakis, all of Rice.

Post Previos sobre los orígenes del biochar y sus propiedades

Biodiversidad, Culturas Prehispánicas y Suelos (¿Mito de los Bosques Primigenios en la Amazonía?)

Cultivos de Tala y Quema en el Amazonía (Chamiceras) y la Calidad del Suelo

Terras Pretas del Amazonas: Distribución y Características Generales

Terras Pretas: Propiedades y Fertilidad (Biochar o Agrichar)

Biocarbón, Fertilidad de Suelos y Cambio Climático

Biochar, Cambio Climático, Secuestro de Carbono, Suelos y Marketing Empresarial

Biochar Personalizados Para todo tipo de Suelos y Cultivos

Fertilizantes Nitrogenados, Óxido Nitroso, Contaminación y Cambio Climático

Biochar, Ecología del Suelo, Cambio Climático y Reducción de las Emisiones de Óxido Nitroso.

El Biochar, Inteligencia Militar, Espionaje Masivo entre las fuerzas del bien y del Mal en el Seno del Suelo

[…] Todo lo que no sabemos del Biochar y ni tan siquiera nos hemos planteado (Una conjetura acerca de su… […]

[…] Todo lo que no sabemos del Biochar y ni tan siquiera nos … […]

[…] Todo lo que no sabemos del Biochar y ni tan siquiera nos hemos planteado (Una conjetura acerca de su… […]