![]()

La Revolución Neolítica de los Organismos del Suelo: Sobre el Ciclo del Nitrógeno, Monocultivos, Hormigas y Bacterias

Por no inventar, ni los monocultivos. El ser humano, con su tecnología, suele redescubrir mecanismos ya desarrollados por otros organismos vivos. Sin embargo, mientras los segundos son sustentables, los nuestros no. Ni siquiera plagiamos bien, como los malos estudiantes. Nuestros cultivos requieren necesariamente (¿?) fertilización, mientras que los de las hormigas y termitas no. Homo sapiens sapiens dedicados a edafólogos descubrieron hace unas décadas la fijación biológica del nitrógeno por los microorganismos (ya sean especies que viven libremente, o asociadas a los sistemas radicales de ciertas plantas vasculares). Sin embargo, las cantidades producidas no eran suficientes con vistas a cubrir sus demandas, derivadas de un desorbitado crecimiento demográfico y excesivo productivismo. En consecuencia, desarrollamos los fertilizantes nitrogenados. Su uso y abuso ha convertido el medio ambiente en una cloaca, alterando seriamente el ciclo del nitrógeno de la biosfera. Diversos expertos opinan que, este último, ha sido afectado más seriamente que el del propio carbono, aunque de momento no nos percatemos de todas las consecuencias. Los dos notas que comentaremos hoy, que dan cuenta de otros tantos artículos de investigación, nos informan de que para otras especies: (i) los monocultivos si pueden ser sustentables durante decenas de millones de años; (ii) que su actividad no solo les basta para subsistir, sino que, regalan nitrógeno a la biosfera, ya que se acumulan evidencias de que los cultivos de hongos llevados a cabo por hormigas y termitas desprenden una enorme cantidad de este elemento en forma asimilable, esencial para el funcionamiento de los ecosistemas tropicales y subtropicales; (iii) al construir sus gigantescos nidos “labran el suelo (bioturbación) de un modo también sustentable, permitiendo el reciclado de nutrientes que, de otro modo, se perderían por los lixiviados pluviales de los sistemas edáficos muy pobres en los mismos y (iv) que las ciudades con millones de individuos, no solo son sustentables, sino incluso beneficiosas para la salud de la biosfera. ¿Han falta más lecciones para ilustrar que andamos por mal camino?

Termitomicetos esparciendo esporas en

las salidas de los termiteros. Fuente: Wikipedia

Ya sé, alegaréis que las grandes diferencias existentes entre estos bobos animales y la superdotada inteligencia humana invalidan tal paralelismo conceptual. Empero a las pruebas me remito. Hormigas y bacterias han sobrevivido durante decenas de millones de años, mientras nosotros vamos caminos de la extinción en unos 10.000 añitos, de no cambiar drásticamente de rumbo.

Las dos noticias extraídas de Sciencedaily espaciadas en el plazo de muy pocos días, dan cuanta de las actividades de hormigas y termitas, así como de su potencial para que puedan edificarse los ecosistemas tropicales y subtropicales que tanto nos fascinan. ¿Cómo serían estos últimos sin la existencia de estos organismos edáficos? Con toda seguridad, muy diferentes. Y aun así, seguimos despreciando la imperiosa necesidad de abordar seriamente un inventario de los seres vivos que habitan en el suelo. ¿No somos imbéciles? Lo que sí ha demostrado el ser humano es que la idiotez e inteligencia pueden cohabitar sin mayores problemas. ¿Ahora bien se puede sobrevivir así? Probablemente tan solo durante un breve lapso de tiempo, si no utilizamos nuestro cerebro y la tecnología derivada de él de una manera más eficiente.

Como señala la primera noticia, tan solo en el bosque amazónico las hormigas cuadruplican la biomasa de todos los demás animales juntos, sin alterar el equilibrio del ecosistema, sino generándole imprescindibles beneficios. ¿Cuánto ascendería tal cifra si se sumaran todos los organismos que viven en el suelo?

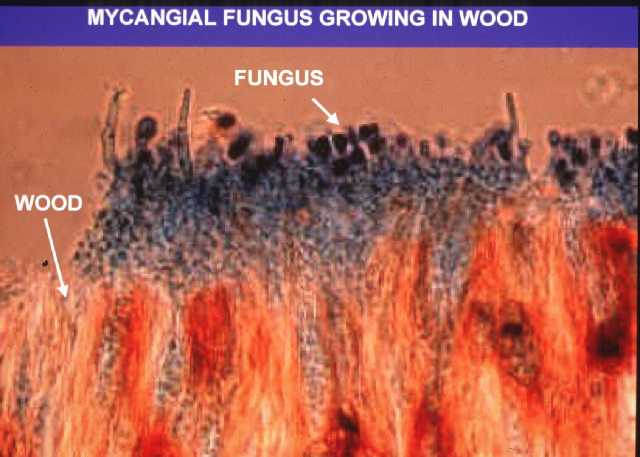

Cultivo de los hongos por las termitas sobre sustrato de madera.

Tanto hormigas como termitas, adolecerían de un alimento de muy mala calidad, y posiblemente cultivos de escasa productividad, si no fuera porque introducen en el sustrato y/o su propio cuerpo bacterias fijadoras de nitrógeno atmosférico. Dicho de otro modo, sin el auxilio de tales organismos simbiónticos ellas mismas tampoco podrían sobrevivir. Obviamente hablamos de mutualismo, pero hay matices. Desde luego, de acuerdo a los estudios que abajo os muestro, la actividad de las bacterias fijadoras de nitrógeno no parece ser accidental. No se comportan como turistas accidentales, precisamente.

Las hormigas, requieren de tales bacterias a la hora de construir los huertos subterráneos de hongos imprescindibles en su alimentación. Cortan y trasladan restos de hojas a sus nidos. Estos servirán, junto a sus propias heces, como sustrato para el cultivo de sus “champiñones”. Pero para que tal actividad tenga éxito, requieren una hasta ahora desconocida simbiosis con las ya mentadas bacterias fijadoras de nitrógeno. Su éxito evolutivo ha sido tan enorme, que se sospecha que tal “agricultura” proporciona la mayor fuente de nitrógeno del suelo en los ambientes tropicales (y en menor medida de otros), un factor otrora limitante para el desarrollo de la vegetación. Como mínimo, tal agricultura a permanecido sin generar problemas (más bien todo lo contrario) desde hace 50 millones de años, alimentando sus ciudades subterráneas compuestas por varios millones de individuos. ¿Esto no es sustentabilidad? Y hablamos de monocultivos.

Termitero Gigante en Australia (Litchfield nat.park).

Pero lo mismo ocurre también con las termitas, también en los neotrópicos, desde hace al menos 30 millones de años. En África, parecen cohabitar unas 330 especies de estos animalitos, sin que se exterminen entre sí, hasta que solo quedara una. Por tanto, como en el caso de las hormigas, se convierten en uno (si no el que más) de los principales recicladotes de nutrientes y materia orgánica en los bosques tropicales húmedos africanos. Al menos en el caso de las termitas, siembran esporas de los denominados “termitomicetos”. Pero no son egoístas, ya que al menos una vez al año, los cuerpos fructíferos de los estos hongos afloran por la boca de los termiteros, dispersando al ambiente sus esporas. Un hecho sorprendente deviene que, de alguna forma, su actividad selecciona tan solo un determinado genotipo del hongo cultivado, entre otros muchos existentes en la naturaleza, algunos de los cuales también están presentes en el sustrato inicial del cultivo. Por sorprendente que parezca, parece existir pues algún tipo de selección genética de los cultivares. Y aquí nosotros redescubriendo la “dinamita”. En mi opinión se necesitan estudios más detallados que nos demuestren como realizan tales tareas, con vistas a aprender algo de la tan cacareada sustentabilidad. Dime de que presumes y te dirá de qué careces.

Os dejo en este enlace una maravillosa descripción que a tal respecto nos realiza Lynn Margulis, la “madre” de la teoría simbiogenética de la evolución. No os la perdáis.

Juan José Ibáñez

Ants Use Bacteria to Make Their Gardens Grow

ScienceDaily (Nov. 24, 2009) — Leaf-cutter ants, which cultivate fungus for food, have many remarkable qualities.

Here’s a new one to add to the list: the ant farmers, like their human counterparts, depend on nitrogen-fixing bacteria to make their gardens grow. The finding, reported Nov. 20 in the journal Science, documents a previously unknown symbiosis between ants and bacteria and provides insight into how leaf-cutter ants have come to dominate the American tropics and subtropics. What’s more, the work, conducted by a team led by University of Wisconsin-Madison bacteriologist Cameron Currie, identifies what is likely the primary source of terrestrial nitrogen in the tropics, a setting where nutrients are otherwise scarce. «Nitrogen is a limiting resource,» says Garret Suen, a UW-Madison postdoctoral fellow and a co-author of the new study. «If you don’t have it, you can’t survive.»

Indeed, the partnership between ant and microbe permits leaf-cutters to be amazingly successful. Their underground nests, some the size of small houses, can harbor millions of inhabitants. In the Amazon forest they comprise four times more biomass than do all land animals combined.

«This is the first indication of bacterial garden symbionts in the fungus-growing ant system,» says Currie, a UW-Madison professor of bacteriology. A critical finding in the new study, according to the Wisconsin scientist, is that the nitrogen, which is extracted from the air by the bacteria, ends up in the ants themselves and, ultimately, benefits the nitrogen-poor ecosystems where the ants thrive.

The fungus-growing ants, Currie notes, are technically herbivores. They make their living by carving up foliage and carrying it back to their nests in endless columns to provide the raw material for the fungus they grow as food. «But plant-feeding insects are known to be nitrogen limited,» explains Currie, «and the plant biomass nitrogen is lower than what the insects need for survival.»

Enter the nitrogen-fixing bacteria, two species of which were isolated in laboratory and field colonies of the ants. But merely finding the bacteria, Suen emphasizes, wasn’t enough. It was necessary to prove that the ants were actually utilizing the nutrient to confirm a true mutualism. «This is important because it could be that the bacteria are fixing nitrogen for themselves and not actually benefiting the ants,» says Suen. «Showing that the nitrogen fixed by the bacteria is incorporated into the ants establishes that these bacteria aren’t just transient visitors.«.

One other type of insect, the termite, has been previously shown to utilize nitrogen-fixing bacteria. And other bacteria-ant symbioses have been documented.

However, the discovery of the nitrogen-fixing mutualism in ants has significant ecological implications given the dominance of ants in virtually all of the word’s terrestrial ecosystems. The new work suggests that an important source of nitrogen in the American tropics and subtropics is derived through the partnership of ant and bacteria. Says Currie: «It is possible that this fixed nitrogen can have ecosystem scale impacts.» The partnership with bacteria, which Currie says could extend back to the origins of the gardening ants some 50 million years ago, confers a competitive edge that has permitted the leaf-cutters to prevail in their environments.

Says Suen: «Without nitrogen, there is no way these guys could achieve such large colony sizes. These ants are one of the most dominant insects in the Neotropics. The ability to have colonies with millions of ants is predicted to require a tremendous amount of nitrogen.»

The new study was funded in part by the U.S. Department of Energy through the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center and the National Science Foundation. In addition to Currie and Suen, the new study was co-authored by Adrian A Pinto-Tomas now of the University of Costa Rica; Mark A. Anderson, Fiona S. T. Chu and W. Wallace Cleland of UW-Madison; and David M. Stevenson and Paul J. Weimer of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Dairy Forage Research Center. (…) Story Source: Adapted from materials provided by University of Wisconsin-Madison, via EurekAlert!, a service of AAAS.

Termites Create Sustainable Monoculture Fungus Farming

ScienceDaily (Nov. 22, 2009) — Food production of modern human societies is mostly based on large-scale monoculture crops, but it now appears that advanced insect societies have the same practice. Our societies took just ten thousand years of (mainly cultural) evolution to adopt this habit and we are far from convinced that it is sustainable. Farming ants and termites had tens of millions of years to evolve their fungus farming systems and here monocultures are apparently evolutionary stable. In a study published in the journal Science, researchers from the Laboratory of Genetics of Wageningen University and the Centre for Social Evolution at the University of Copenhagen take significant steps to resolve this puzzle.

The fungus-growing termites of the old-world tropics build impressive mounds consisting of thousands of workers and soldiers. These societies domesticated African Termitomyces mushrooms more than 30 million years ago and became obligatorily dependent on farming their own fungal food in their often gigantic nest mounds. The termite fungus-farming symbiosis had a single African rain-forest origin and now comprises ca 330 species. It is of major ecological importance for decomposition and mineral cycling. A colony-founding termite queen and king normally do not acquire their first garden until they have raised the first workers. These helpers collect Termitomyces spores while foraging, together with the plant material that they defecate in the nest to establish a garden substrate. These spores are amply available because the fungus gardens produce large mushrooms once a year on top of the termite mounds.

However, this farming practice offers a paradox: Evolutionary theory predicts that symbioses with multiple lineages per colony should be unstable, because these genotypes can be expected to compete for making mushrooms rather than collaborate to serve the termite farmers. The new study shows that a very special mechanism is in place to prevent this from happening. All colonies from which multiple fungal samples were genetically analyzed contained only a single fungal genotype in spite of gardens having been initiated from at least two and probably many more genetically different spores.

Duur Aanen, Koos Boomsma and their respective colleagues in Wageningen and Copenhagen show that genotypes that happen to be common in a garden, become even more common at the expense of rarer genotypes. This happens not because common genotypes are better direct competitors, but because they have a higher chance of having an identical genotype as neighbor. Every time this happens, such genetically identical mycelia merge, which enhances the efficiency by which they produce asexual spores that the termites eat and deposit in new garden material of the colony. This process of positive reinforcement makes every colony end up with a life-time commitment to a single fungal symbiont in spite of the population at large having many fungal genotypes. (…) Story Source: Adapted from materials provided by Wageningen University and Research Centre, via AlphaGalileo.

[…] Hoy albergo aun menos dudas. Del mismo modo, también os informamos en nuestra entrega “La Revolución Neolítica de los Organismos del Suelo: Sobre el Ciclo del Nitrógeno, Monocultivos, …” como, mediante simbiosis con las bacterias, diversos tipos de insectos sociales enriquecen el […]

[…] epifititas, invertebrados aéreos e invertebrados edáficos (muchos de los cuales resultan ser ingenieros del suelo). Las repercusiones de tal hallazgo son múltiples, variadas y relevantes. Indiquemos también que […]

[…] en estudiarlo. Ahora resulta que también lleva a cabo sorprendentes prácticas agrarias como las hormigas que habitan en el suelo e incluso las termitas. En cualquier caso, la lista no acaba aquí, como puede observarse en el […]

[…] La Revolución Neolítica de los Organismos del Suelo: Sobre el Ciclo del Nitrógeno, Monocultivos, … […]

[…] La Revolución Neolítica de los Organismos del Suelo: Sobre el Ciclo del Nitrógeno, Monocultivos, … […]

[…] lignocelulósicos. En el suelo, estos son degradados rápidamente y más aún en presencia de ciertos ingenieros del suelo, como lo son las hormigas y termitas. El estudio que os mostramos hoy (El intestino de termitas tiene un secreto para descomponer la […]

[…] La Revolución Neolítica de los Organismos del Suelo: Sobre el Ciclo del Nitrógeno, Monocultivos, … […]