![]()

Las Sabanas y su Fertilidad: La Biotecnología Natural de los Ingenieros del Suelo

¿Cuáles son las causas que determinan la estructura de las sabanas africanas? ¿De donde procede su fertilidad? ¿Qué factor o factores condicionan su productividad? Un estudio recientemente publicado en PloS Biology (revista en acceso abierto) muestra unos resultados que os sorprenderán a la mayoría de vosotros. El secreto se encuentra en uno de los organismos del suelo a los que los edafólogos denominamos ingenieros. Hablamos de las termitas. Según los autores, y los resultados son espectaculares, estos organismos y las estructuras que generan dan cuenta de los aspectos fundamentales de la estructura y dinámica de estos ecosistemas. Su trabajo de biotecnología natural genera una fertilidad estructurada por la cuasi-cristalina configuración espacial de sus habitáculos. Cuanto más entendamos los suelos, mejor comprenderemos los ecosistemas.

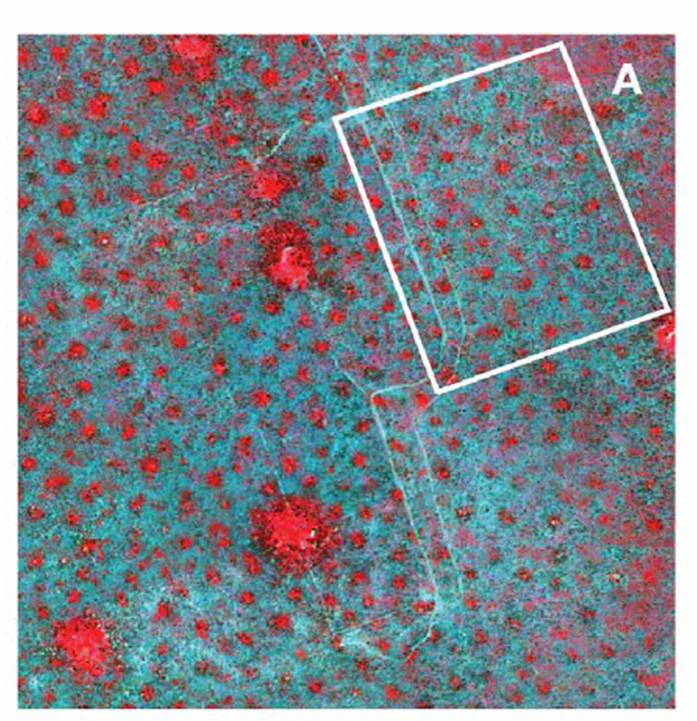

Geometría cuasi-cristalina de la disposición de los termiteros en la sabana. Fuente Plos Biology (ver enlace abajo)

Personalmente, a mi no me extraña. Es una lástima que el sesgo agronómico de la edafología nos auto-margine de estos estudios. Podemos aportar mucho más a la ecología, cambio climático y otras ciencias mediáticas de lo que lo hacemos hoy en día. Y parte del problema se encuentra en nuestra propia inercia.

Las termitas, a la hora de edificar sus termiteros, remozan los perfiles del suelo a lo largo de varios metros de profundidad. Se trata de lo que denominamos haploidización mediante bioturbación. Ya comentamos en nuestro post “Laterización: Génesis de Oxisoles, y Termitas”, que la posible génesis de suelos muy homogéneos, como los Oxisoles (Ferralsoles) pudiera deberse a este tipo de bioturbación. Hoy albergo aun menos dudas. Del mismo modo, también os informamos en nuestra entrega “La Revolución Neolítica de los Organismos del Suelo: Sobre el Ciclo del Nitrógeno, Monocultivos, Hormigas y Bacterias” como, mediante simbiosis con las bacterias, diversos tipos de insectos sociales enriquecen el medio edáfico en uno de sus factores más limitantes para el desarrollo vegetal. Hablamos del nitrógeno. Es una lástima que entre los autores del artículo que da pie a este post no hubiera un edafólogo, ya que estos investigadores se lían un poco a la hora de explicar el efecto de la bioturbación. Así por ejemplo, comentan que devuelven a la superficie del suelo elementos texturales gruesos que mejoran su estructura y favorecen la infiltración del agua, que de este modo tiende a impedir su encharcamiento en la estación de las lluvias. Puede ser. Sin embargo, parte de las fracciones texturales gruesas bien pudieren ser pseudolimos, es decir partículas del tamaño del limo que en realidad son agregados de arcillas fuertemente unidas entre si por las abundantes cantidades de sesquióxidos de hierro que caracterizan a los Oxisoles o Ferralsoles. Se trata de suelos pobres en nutrientes, por lo que cualquier “ayudita” por parte de los ingenieros del suelo causa un gran efecto en su fertilidad.

Pues bien, la productividad primaria y biomasa de la vegetación aumenta conforme uno se acerca a la boca de los termiteros. Y así, arrastra a todos los restantes elementos de la cadena trófica. Empero la disposición de estas megapolis invisibles bajo nuestros pies (bioingeniería edáfica) resulta ser extremadamente regular, es decir no aleatoria. Su disposición espacial emula a una retícula cristalina, cuyos nodos resultan ser los mencionados termiteros. Se trata de una disposición óptima con vistas a optimizar los efectos de tales colonias de insectos sociales en ambientes áridos y semiáridos (ver post: Arquitectura de los Suelos y la Vegetación en los Ambientes Áridos y Semiáridos). Empero si el terreno dista mucho de ser llano, otras configuraciones surgirían, como ya vimos en aquella ocasión.

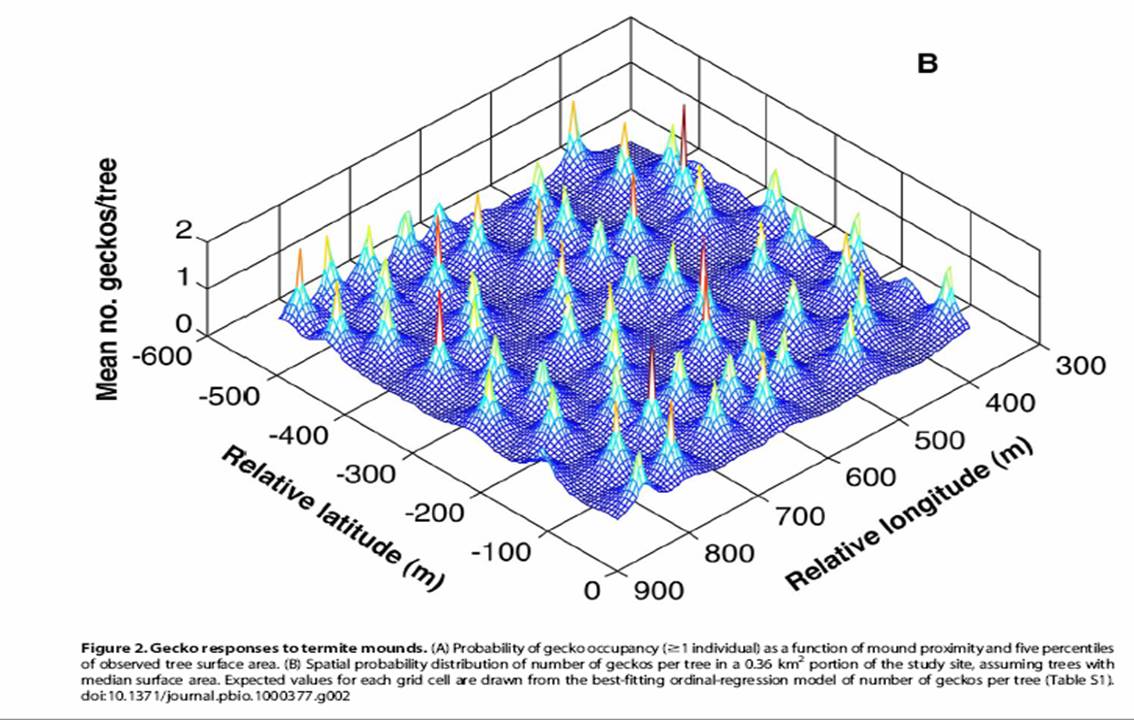

Incremento de productividad generada por la geometría cuasi-cristalina de la disposición de los termiteros en la sabana. Fuente Plos Biology (ver enlace abajo)

Resulta increíble, como se indica en la noticia, que las termitas se hayan tradicionalmente considerado como un serio problema, cuando no una indeseable plaga para la agricultura y la ganadería de los ambientes sabanoides, cuando en realidad su actividad deviene en una “bendición”. Tal hecho demuestra la vital importancia de seguir profundizando en la estructura y dinámica de los sistemas edáficos, así como de sus pequeños biotecnólogos ecosistémicos.

En cualquier caso, no debemos olvidarnos de esos gigantones mamíferos a los que llamamos elefantes. Ellos son los que permiten la apertura del bosque cerrado para generar pastos arbolados, cuando estos desaparecen los bosques de acacias vuelven a cerrarse, perdiéndose gran parte de la espectacular belleza que les confiere esos magníficos ensamblajes faunísticos que atesoran, como ya os explicamos al hablar de las Sabanas Africanas.

Juan José Ibáñez

El Trabajo Original puede bajarse pinchando en título del trabajo, es decir, a renglón seguido.

Spatial Pattern Enhances Ecosystem Functioning in an African Savanna

Otros post previos relacionados con el tema

Arquitectura de los Suelos y la Vegetación en los Ambientes Áridos y Semiáridos

Laterización: Génesis de Oxisoles, Ultisoles y las Termitas

Horizonación versus Haploidización: Mecanismos Naturales de Destrucción de los Horizontes del Suelo

Nota de Prensa

The Star Of Africa’s Savanna Ecosystems May Be The Lowly Termite

Terradaily: by Staff Writers; Cambridge, MA (SPX) Jun 01, 2010

The majestic animals most closely associated with the African savanna, fierce lions, massive elephants, towering giraffes may be relatively minor players when it comes to shaping the ecosystem.

Termite mounds, seen here in Kenya’s Masai Mara as an oasis of green in a sea of brown, help support savanna biodiversity at all levels, from tiny insects to this family of cheetahs.

The real king of the savanna appears to be the termite, say ecologists who’ve found that these humble creatures contribute mightily to grassland productivity in central Kenya via a network of uniformly distributed colonies.

Termite mounds greatly enhance plant and animal activity at the local level, while their even distribution over a larger area maximizes ecosystem-wide productivity. The finding, published this week in the journal PLoS Biology, affirms a counterintuitive approach to population ecology: Often it’s the small things that matter most.

«It’s not always the charismatic predators – animals like lions and leopards – that exert the greatest control on populations,» says Robert M. Pringle, a research fellow at Harvard University. «As E.O. Wilson likes to point out, in many respects it’s the little things that run the world. In the case of the savanna, it appears these termites have tremendous influence and are central to the functioning of this ecosystem.»

Prior research on the Kenya dwarf gecko initially drew Pringle’s attention to the peculiar role of grassy termite mounds, which in this part of Kenya are some 10 meters in diameter and spaced some 60 to 100 meters apart. Each mound teems with millions of termites, who build the mounds over the course of centuries.

After observing unexpectedly high numbers of lizards in the vicinity of mounds, Pringle and his colleagues began to quantify ecological productivity relative to mound density. They found that each mound supported dense aggregations of flora and fauna: Plants grew more rapidly the closer they were to mounds, and animal populations and reproductive rates fell off appreciably with greater distance. What was observed on the ground was even clearer in satellite imagery. Each mound – relatively inconspicuous on the Kenyan grassland – stood at the center of a burst of floral productivity.

More importantly, these bursts were highly organized in relation to one another, evenly dispersed as if squares on a checkerboard. The result, says Pringle, is an optimized network of plant and animal output closely tied to the ordered distribution of termite mounds.

«In essence, the highly regular spatial pattern of fertile mounds generated by termites actually increases overall levels of ecosystem production. And it does so in such a profound way,» says Todd M. Palmer, assistant professor of biology at the University of Florida and an affiliate of the Mpala Research Centre in Nanyuki, Kenya. «Seen from above, the grid-work of termite mounds in the savanna is not just a pretty picture. The over-dispersion, or regular distribution of these termite mounds, plays an important role in elevating the services this ecosystem provides.»

The mechanism through which termite activity is transformed into far-reaching effects on the ecosystem is a complex one. Pringle and Palmer suspect termites import coarse particles into the otherwise fine soil in the vicinity of their mounds. These coarser particles promote water infiltration of the soil, even as they discourage disruptive shrinking and swelling of topsoil in response to precipitation or drought. The mounds also show elevated levels of nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen. All this beneficial soil alteration appears to directly and indirectly mold ecosystem services far beyond the immediate vicinity of the mound.

While further studies will explore the mechanism through which these spatial patterns of termite mounds emerge, Pringle and Palmer suggest that the present work has implications beyond the basic questions of ecology. «Termites are typically viewed as pests, and as threats to agricultural and livestock production,» Pringle says. «But productivity – of both wild and human-dominated landscapes – may be more intricately tied to the pattern-generating organisms of the larger natural landscape than is commonly understood.»

The findings also have important implications for conservation, Palmer says. «As we think restoring degraded ecosystems, as we think about restoring coral reefs, or restoring plant communities, this over-dispersed pattern is teaching us something,» he says. «It’s saying we might want to think about doing our coral restoration or plant restoration in a way that takes advantage of this ecosystem productivity enhancing phenomenon.»

Pringle and Palmer’s co-authors on the PLoS Biology paper are Daniel F. Doak of the Mpala Research Centre and the University of Wyoming; Alison K. Brody of the Mpala Research Centre and the University of Vermont; and Rudy Jocque of the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium. Their work was supported by the Sherwood Family Foundation and the National Science Foundation.

Resumen del Trabajo Original

Abstract

The finding that regular spatial patterns can emerge in nature from local interactions between organisms has prompted a search for the ecological importance of these patterns. Theoretical models have predicted that patterning may have positive emergent effects on fundamental ecosystem functions, such as productivity. We provide empirical support for this prediction. In dryland ecosystems, termite mounds are often hotspots of plant growth (primary productivity). Using detailed observations and manipulative experiments in an African savanna, we show that these mounds are also local hotspots of animal abundance (secondary and tertiary productivity): insect abundance and biomass decreased with distance from the nearest termite mound, as did the abundance, biomass, and reproductive output of insect-eating predators. Null-model analyses indicated that at the landscape scale, the evenly spaced distribution of termite mounds produced dramatically greater abundance, biomass, and reproductive output of consumers across trophic levels than would be obtained inlandscapes with randomly distributed mounds. These emergent properties of spatial pattern arose because the average distance from an arbitrarily chosen point to the nearest feature in a landscape is minimized in landscapes where the features are hyper-dispersed (i.e., uniformly spaced). This suggests that the linkage between patterning and ecosystem functioning will be common to systems spanning the range of human management intensities. The centrality of spatial pattern to system-wide biomass accumulation underscores the need to conserve pattern-generating organisms and mechanisms, and to incorporate landscape patterning in efforts to restore degraded habitats and maximize the delivery of ecosystem services.

(…) with the result that ecosystem-wide productivity is greater under the actual distribution of mounds than it would be if the same number of mounds were randomly situated.

[…] un sorprendente caso emparentado con las estructuras y procesos que escribimos en un post previo (Las Sabanas y su Fertilidad: La Biotecnología Natural de los Ingenieros del Suelo). La novedad estriba en que hoy mostraremos como una etnia de la cultura de los Arahuacos, en la […]

[…] casi todo. Sin embargo, resultan ser, como las termitas y ciertos tipos de hormigas unos ingenieros del suelo formidables, favoreciendo la porosidad, capacidad de infiltración, descomposición de la materia […]

[…] horizontes del perfil. Se trata pues de las tareas que se les atribuyen a los denominados ingenieros del suelo, gracias a su potencial de haploidización-bioturbación. En otras palabras, las especies anécicas […]

[…] también lleva a cabo sorprendentes prácticas agrarias como las hormigas que habitan en el suelo e incluso las termitas. En cualquier caso, la lista no acaba aquí, como puede observarse en el resumen del trabajo […]

Buenas,

Enhorabuena por el blog divulgativo. Lo he encontrado buscando información acerca de los efectos de las hormigas y las termitas sobre el suelo, tanto positivos como negativos. Me preguntaba si usted podría ayudarme recomendándome autores autores o bibliografía al respecto.

Muchas gracias,

Manuel Ramos

[…] Las Sabanas y su Fertilidad: La Biotecnología Natural de los Ingenieros del Suelo […]

[…] diversidad, el paisaje carecería de puntos calientes de esta escala“, dijo Ambrose. “Los hotspots más grandes habrían tenido solo unos pocos metros de diámetro, centrados en los mont…. Los patrones de vegetación habrían sido mucho más uniformes y el ecosistema habría sido más […]