![]()

La Vida Reticulada. Una Nueva Genética de la Biosfera

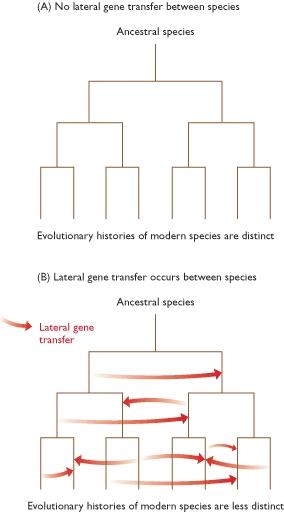

¿Sabe usted lo que contienen sus genes? ¿Son de mamá y de papá, exclusivamente? Pues va a ser que no. Posiblemente su genoma pueda albergar DNA de virus, bacterias, hongos, insectos y de algunos otros bichos parásitos que infectaron a sus progenitores, más o menos ancestrales, aunque también de simbiontes. El ideal neodarvinista de la herencia vertical, como motor de la evolución biológica, parece desmoronarse. La vida probablemente deba analizarse como una retícula o red de intercambio del material hereditario. Sería algo así como la estructura de Internet, con grandes autopistas jerárquicas de herencia vertical y pequeños atajos entre ellas de otra de naturaleza horizontal. Y eso fundamentalmente en los seres superiores o eucariotas, por cuanto en el mundo de los procariontes tal jerarquía se difumina, incluso podría diluirse por completo. Día a día, se van descubriendo más casos de la transferencia horizontal de genes entre los taxa más dispares.

Sabíamos que ciertos segmentos de virus se insertan en nuestro genoma, o que este tipo de herencia es común en el mundo microbiano procariótico. Hace pocas semanas ya os anunciamos en otro post como los hongos, organismos eucariotas, pueden llegar a trasferirse horizontalmente entre taxa distintos cromosomas enteros. Investigaciones recientes dicen haber comprobado la presencia del mismo mecanismo (en este caso genes) entre parásitos y mamíferos. Incluso ciertos insectos parecen sintetizar compuestos esenciales, que solo se creía posible que lo hicieran vegetales y hongos, gracias a que estos últimos les han regalado las secuencias necesarias de DNA.

Sabe usted lo que son los tranposones o genes saltarines. Es una parte de este rompecabezas, aunque hay mucho más que tener en cuenta. Como defienden los autores de uno de los estudios que abajo os incluimos, cuando se descubre en nuevo mecanismo puede parecernos como algo extraordinario, singular o extremadamente raro. Sin embargo, abre la puerta a que otros científicos urgen en tales rarezas, terminando por percatarse que resultan ser de lo más ubicuo. De momento, los simbiontes y parásitos parecen estar en buena posición de la parrilla de salida de tales tipos de transferencias hereditarias, a las que algunos llamarán, con mala intención, “interferencias”. Y así la estructura de su genoma cambia y como corolario sus cauces evolutivos. Esta perspectiva es acusadamente distinta de la que defiende la ortodoxia darvinista.

No os voy a desmenuzar las noticias que os muestro abajo en suahili, sino que intentaré tan solo explicar su contenido en forma de metáfora.

La vida Reticulada. Fuente: Panda’s Thumb

En el mundo de los microorganismos procariotas, cada vez resulta más evidente que la herencia es tanto vertical como horizontal, a modo de una red en que las carreteras son más o menos de igual anchura. En los eucariotas, y especialmente conforme aumenta su complejidad, la herencia vertical (de padres a hijos) deviene en dominante. De hecho, la ortodoxia neodarviniana nos dice que es exclusiva. Empero la vida se salta a la torera reglas tan ramplonas. La herencia vertical sería algo así como grandes autopistas independientes por donde circulan la mayor parte de los genes de los individuos, generación tras generación. Sin embargo, de vez en cuando, algunos toman un atajo vertiendo parte de su material en otra autopista por carreteras o caminos vecinales. La pregunta del millón es averiguar la frecuencia con la que acaece tal evento. Sabemos que no parece ser muy usual, aunque varía entre las diferentes formas de vida. Sin embargo, lo realmente intrigante es hasta que punto tal “diversión” modifica la evolución de las especies, ya que el tema no resulta ser tanto de cantidad como de calidad o importancia.

Volvemos a reiterar que la historia de las ciencias nos enseña que, cuando se abre una nueva vía mediante un descubrimiento inesperado, detrás puede llegar un torrente que modifica drásticamente el paisaje científico anterior. El tiempo dirá. Personalmente tengo la impresión que el neodarvinismo, tal como lo defienden sus ultraortodoxos califas, tiene los días contados.

Juan José Ibáñez

Ver también el post

La Extraordinaria Genética de los Microorganismos del Suelo

Scientists Uncover Transfer of Genetic Material Between Blood-Sucking Insect and Mammals

ScienceDaily (Apr. 30, 2010) — Researchers at The University of Texas at Arlington have found the first solid evidence of horizontal DNA transfer, the movement of genetic material among non-mating species, between parasitic invertebrates and some of their vertebrate hosts.

The findings are published in the April 28 issue of the journal Nature, one of the world’s foremost scientific journals.

Genome biologist Cédric Feschotte and postdoctoral researchers Clément Gilbert and Sarah Schaack found evidence of horizontal transfer of transposon from a South American blood-sucking bug and a pond snail to their hosts. A transposon is a segment of DNA that can replicate itself and move around to different positions within the genome. Transposons can cause mutations, change the amount of DNA in the cell and dramatically influence the structure and function of the genomes where they reside.

«Since these bugs frequently feed on humans, it is conceivable that bugs and humans may have exchanged DNA through the mechanism we uncovered. Detecting recent transfers to humans would require examining people that have been exposed to the bugs for thousands of years, such as native South American populations,» Feschotte said.

Data on the insect and the snail provide strong evidence for the previously hypothesized role of host-parasite interactions in facilitating horizontal transfer of genetic material. Additionally, the large amount of DNA generated by the horizontally transferred transposons supports the idea that the exchange of genetic material between hosts and parasites influences their genomic evolution.

«It’s not a smoking gun, but it is as close to it as you can get,» Feschotte said. he infected blood-sucking triatomine, causes Chagas disease by passing trypanosomes (parasitic protozoa) to its host. Researchers found the bug shared transposon DNA with some hosts, namely the opossum and the squirrel monkey. The transposons found in the insect are 98 percent identical to those of its mammal hosts.

The researchers also identified members of what Feschotte calls space invader transposons in the genome of Lymnaea stagnalis, a pond snail that acts as an intermediate host for trematode worms, a parasite to a wide range of mammals.

The long-held theory is that mammals obtain genes vertically, or handed down from parents to offspring. Bacteria receive their genes vertically and also horizontally, passed from one unrelated individual to another or even between different species. Such lateral gene transfers are frequent in bacteria and essential for rapid adaptation to environmental and physiological challenges, such as exposure to antibiotics.

Until recently, it was not known horizontal transfer could propel the evolution of complex multicellular organisms like mammals. In 2008, Feschotte and his colleagues published the first unequivocal evidence of horizontal DNA transfer.

Millions of years ago, tranposons jumped sideways into several mammalian species. The transposon integrated itself into the chromosomes of germ cells, ensuring it would be passed onto future generations. Thus, parts of those mammals’ DNA did not descend from their common ancestors, but were acquired laterally from another species.

The actual means by which transposons can spread across widely diverse species has remained a mystery.

«When you are trying to understand something that occurred over thousands or millions of years ago, it is not possible to set up a laboratory experiment to replicate what happened in nature,» Feschotte said.

Instead, the researchers made their discovery using computer programs designed to compare the distribution of mobile genetic elements among the 102 animals for which entire genome sequences are currently available. Paul J. Brindley of George Washington University Medical Center in Washington, D.C., contributed tissues and DNA used to confirm experimentally the computational predictions of Feschotte’s team.

When the human genome was sequenced a decade ago, researchers found that nearly half of the human genome is derived from transposons, so this new knowledge has important ramifications for understanding the genetics of humans and other mammals.

Feschotte’s research is representative of the cutting edge research that is propelling UT Arlington on its mission of becoming a nationally recognized research institution.

Story Source: Adapted from materials provided by University of Texas at Arlington.

Journal Reference: Clément Gilbert, Sarah Schaack, John K. Pace II, Paul J. Brindley, Cédric Feschotte. A role for host-parasite interactions in the horizontal transfer of transposons across phyla. Nature, 2010; 464 (7293): 1347 DOI: 10.1038/

First Case of Animals Making Their Own Essential Nutrients: Carotenoids

ScienceDaily (Apr. 30, 2010) — The insects known as aphids can make their own essential nutrients called carotenoids, according to University of Arizona researchers.

No other animals are known to make the potent antioxidants. Until now scientists thought the only way animals could obtain the orangey-red compounds was from their diet.

«It is written everywhere that animals do not make carotenoids,» said Nancy Moran, leader of the UA team that overturned the conventional wisdom.

Carotenoids are building blocks for molecules crucial for vision, healthy skin, bone growth and other key physiological functions. Beta-carotene, the pigment that makes carrots orange, is the building block for Vitamin A.

«Once you start realizing how widespread carotenoids are, you realize that they’re everywhere in life,» said Moran, a UA Regents’ Professor of ecology and evolutionary biology.

«The yellow color in egg yolks, the pink in shrimp and salmon, the pink in flamingos, tomatoes, carrots, peppers, Mexican poppies, marigolds — the yellow, orange, and red are all carotenoids.»

Moran and her co-author Tyler Jarvik also figured out how the aphids they studied, known as pea aphids, acquired the ability to make carotenoids. «What happened is a fungal gene got into an aphid and was copied,» Moran said. She added that, although gene transfers between microorganisms are common, finding a functional fungus gene as part of an animal’s DNA is a first.

«Animals have a lot of requirements that reflect ancestral gene loss. This is why we require so many amino acids and vitamins in the diet,» she said. «Until now it has been thought that there is simply no way to regain these lost capabilities. But this case in aphids shows that it is indeed possible to acquire the capacity to make needed compounds.

«Possibly this will be an extraordinarily rare case. But so far in genomic studies, a single initial case usually turns out to be only an example of something more widespread.»

She and Jarvik, a research specialist in UA’s department of chemistry and biochemistry, report their discovery in the paper, «Lateral Transfer of Genes from Fungi Underlies Carotenoid Production in Aphids,» to be published in the April 30 issue of the journal Science. The National Science Foundation funded the research.

A lucky accident in the lab plus the recent sequencing of the pea aphid genome made the discovery possible, Moran said.

Pea aphids, known to scientists as Acyrthosiphon pisum, are either red or green. Aphids are clonal — the mothers give birth to daughters that are genetically identical to their mothers. So when an aphid in the Moran lab’s red 5A strain began giving birth to yellowish-green babies, Moran and her colleagues knew they were looking at the results of a mutation.

«We named it 5AY for yellowish,» she said. «That yellowish mutant happened in 2007. We just kept the strain as a sort of pet in the lab. I figured that one day we’d figure out how that happened.»

Symbiotic bacteria live within aphids in specialized cells. The bacteria, which are passed from mother to babies, supply the insects with crucial nutrition. If their bacteria die, the aphids die.

Moran, who has been studying the pea aphid-bacteria system for decades, already knew the three main species of symbiotic bacteria did not make carotenoids.

She also was pretty sure the aphids didn’t get their carotenoids from their diet. Aphids eat by sucking the phloem sap from plants, but the sap is carotenoid-poor. In addition, the carotenoids in the aphids were different from those usually found in plants. In late 2009, after the complete DNA sequence of the pea aphid became available to researchers, she decided to search it for carotenoid genes.

All organisms use the same biosynthetic pathway to make carotenoids, which made searching for carotenoid genes straightforward, she said.

Lucky for Moran, the researchers who sequenced the pea aphid genome used red aphids, which have an extra copy of the carotenoid gene, making the gene causing the red color easier to find.

Next, she figured out whether the genes were from pea aphid DNA or from uncommon symbiotic bacteria or were just contamination from fungi in the sample.

In the laboratory, Moran and Jarvik found eliminating the symbiotic bacteria from a strain of aphids did not change the color of the offspring, meaning the symbiotic bacteria were not the source of the red color.

In addition, tracing the lineages of the red, green and yellow strains of aphids showed the colors had a Mendelian inheritance pattern, indicating the DNA that coded for red was part of the aphid’s DNA.

That inheritance pattern also fit with another team’s research that suggested both colors were present in nature because red aphids are more susceptible to parasitic wasps, whereas green aphids are more susceptible to predators such as lady-bird beetles.

The final piece of the puzzle was figuring out where the genes came from. The particular sequence of aphid DNA that coded for carotenoids differed from bacterial carotenoid genes and matched those from some fungi.

Moran said a long-term association between aphids and pathogenic fungi could make such a gene transfer possible.

The discovery illustrates «the interweaving of organisms and their genomes over time and their merging in different ways,» she said. «The distinctness of different genomes and organisms and lineages is much less than we thought.«

Story Source: Adapted from materials provided by University of Arizona. Original article written by Mari N. Jensen.

Journal Reference:Nancy A. Moran and Tyler Jarvik. Lateral Transfer of Genes from Fungi Underlies Carotenoid Production in Aphids. Science, 30 April 2010 328: 624-627 DOI: 10.1126/science.1187113

Excelente lectura para la mañana de un domingo primaveral.

Lo que sorprende es cómo los autores de estos artículos no incluyen en su discusión aspectos clave como por ejemplo la crítica de determinados aspectos del darwinimo (gradualismo, mutación puntual, mutación al azar,….).

Goodbye, Darwin!

[…] su momento (fijaros siempre en las fechas de nuestras entregas). Parece que nuestra hipótesis: “La Vida Reticulada. Una Nueva Genética de la Biosfera” sigue sumando evidencias. La genética de los microorganismos del suelo (incluyendo a microfauna […]

Wow! Thank you! I continuously needed to write on my site something like that. Can I take a portion of your post to my blog?

[…] secretos la facilidad para el flujo horizontal de genes que acaece en el suelo (ver nuestro post: la vida reticulada: una nueva genética de la biosfera). Eso si, el mal uso de los recursos edáficos también induce la emergencia de las graves y […]

[…] La Vida Reticulada. Una Nueva Genética de la Biosfera […]

[…] decir de la biodiversidad. Y así, entre otros constructos mentales también podemos concebir una vida reticulada. Para ciertos científicos las especies son picos de un continuo (como lo serían las células no […]

[…] el árbol filogenético a modo de gigantesca red, corroborando entonces nuestra visión previa de la vida reticulada y su evolución a lo largo de la historia de la Tierra. Nosotros mismos, nuestros genomas, son […]

[…] La Vida Reticulada. Una Nueva Genética de la Biosfera […]