![]()

El hombre que escribía en los puentes

Esta entrada está dedicada a la figura de William R. Hamilton, el inventor de los cuaternios que usó Maxwell para escribir sus ecuaciones y que hizo además grandes contribuciones a la Óptica.

16 de octubre de 1846, un hombre pasea con su esposa por las orillas del Canal Real de Dublín (Irlanda) y empieza a cruzar el puente de Broom. Es William Rowen Hamilton, pensando en un problema matemático. De repente se detiene, la inspiración ha llegado a su mente: acaba de inventar los cuaternios. Él mismo lo cuenta en esta carta a su hijo Archibald:

Letter dated August 5, 1865.

MY DEAR ARCHIBALD – (1) I had been wishing for an occasion of corresponding a little with you on QUATERNIONS: and such now presents itself, by your mentioning in your note of yesterday, received this morning, that you «have been reflecting on several points connected with them» (the quaternions), «particularly on the Multiplication of Vectors.’’

(2) No more important, or indeed fundamental question, in the whole Theory of Quaternions, can be proposed than that which thus inquires What is such MULTIPLICATION? What are its Rules, its Objects, its Results? What Analogies exist between it and other Operations, which have received the same general Name? And finally, what is (if any) its Utility?

(3) If I may be allowed to speak of myself in connexion with the subject, I might do so in a way which would bring you in, by referring to an ante-quaternionic time, when you were a mere child, but had caught from me the conception of a Vector, as represented by a Triplet: and indeed I happen to be able to put the finger of memory upon the year and month – October, 1843 – when having recently returned from visits to Cork and Parsonstown, connected with a meeting of the British Association, the desire to discover the laws of the multiplication referred to regained with me a certain strength and earnestness, which had for years been dormant, but was then on the point of being gratified, and was occasionally talked of with you. Every morning in the early part of the above-cited month, on my coming down to breakfast, your (then) little brother William Edwin, and yourself, used to ask me, «Well, Papa, can you multiply triplets»? Whereto I was always obliged to reply, with a sad shake of the head: «No, I can only add and subtract them.»

(4) But on the 16th day of the same month – which happened to be a Monday, and a Council day of the Royal Irish Academy – I was walking in to attend and preside, and your mother was walking with me, along the Royal Canal, to which she had perhaps driven; and although she talked with me now and then, yet an under-current of thought was going on in my mind, which gave at last a result, whereof it is not too much to say that I felt at once the importance. An electric circuit seemed to close; and a spark flashed forth, the herald (as I foresaw, immediately) of many long years to come of definitely directed thought and work, by myself if spared, and at all events on the part of others, if I should even be allowed to live long enough distinctly to communicate the discovery. Nor could I resist the impulse – unphilosophical as it may have been – to cut with a knife on a stone of Brougham Bridge, as we passed it, the fundamental formula with the symbols, i, j, k; namely,

i2 = j2 = k2 = ijk = -1

which contains the Solution of the Problem, but of course, as an inscription, has long since mouldered away. A more durable notice remains, however, on the Council Books of the Academy for that day (October 16th, 1843), which records the fact, that I then asked for and obtained leave to read a Paper on Quaternions, at the First General Meeting of the session: which reading took place accordingly, on Monday the 13th of the November following.

With this quaternion of paragraphs I close this letter I.; but I hope to follow it up very shortly with another.

Your affectionate father,

WILLIAM ROWAN HAMILTON

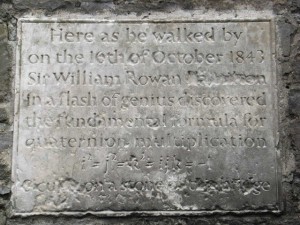

Una placa conmemora ese hecho, placa en la que se puede leer:

Una placa conmemora ese hecho, placa en la que se puede leer:

Here, as he walked by

on the 16th of October 1843,

Sir William Rowan Hamilton,

in a flash of genius, discovered

the fundamental formula for

i² = j² = k² = ijk = -1

& cut it on a stone of this bridge.

Esta placa fue inaugurada por Éamon de Valera, presidente de Irlanda, también matemático y estudioso de los cuaternios, el 13 de noviembre de 1958. Cada año, se repite el recorrido de Hamilton por el canal Real en conmemoración de ese hecho tan notable.

Repasemos brevemente la biografía de Hamilton. Nació y murió en Dublín (1805-1865). Fue un niño prodigio, tanto en matemáticas como en lenguas clásicas. Ya a la edad de 8 años disputó un torneo de cálculo en Dublín con el prodigio norteamericano Zerah Colburn, torneo que perdió y a raíz del cuál decidió dedicarle más tiempo a las matemáticas. No desaprovechó el tiempo, y ya a la edad de 22 años fue nombrado profesor de Astronomía (antes de terminar el grado).

Los grandes resultados de Hamilton fueron en la llamada Óptica Geométrica, la Mecánica Clásica, y el álgebra de cuaternios, entre otros. No publicó sin embargo muchos artículos a pesar de haber obtenido numerosos resultados porque era muy perfeccionista. Al contrario, escribía largas cartas en las que discutía los problemas que estaba abordando.

A Hamilton se le debe el llamado principio de Hamilton que proporciona las ecuaciones de Euler-Lagrange usando Cálculo de Variaciones. También llevan su nombre las ecuaciones de Hamilton

En estas ecuaciones aparecen:

Posiciones q

Momentos p

Hamiltoniano H = H (q, p)

H = K + V (energía total o energía hamiltoniana).

El álgebra de los cuaternios es su gran creación, y es una extensión de los números complejos a cuatro dimensiones.

Otro de sus logros es la llamada ecuación de Hamilton-Jacobi, esencial para estudiar la integrabilidad de los sistemas mecánicos.

Su notoriedad en Irlanda es enorme, como muestran estos sellos que aquí reproducimos

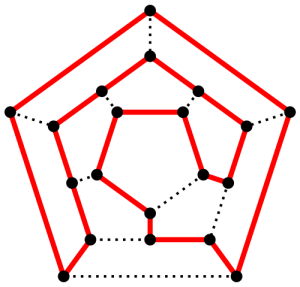

Mas nociones matemáticas llevan su nombre, como la de camino hamiltoniano, que es un camino de un grafo, una sucesión de aristas adyacentes, que pasa por todos los vértices del grafo una sola vez. Si además el último vértice visitado es adyacente al primero, el camino es un ciclo hamiltoniano. Hamilton, de hecho, inventó un juego que consistía en encontrar un ciclo hamiltoniano en las aristas de un grafo de un dodecaedro. Hamilton resolvió este problema usando cuaternios, aunque su solución no era generalizable a todos los grafos.

Sobre Óptica, Hamilton desarrolló su tratado Theory of Systems of Rays. La comprobación experimental unos meses más tarde de su teoría a cargo de Humphrey Lloyd, le proporcionó una gran fama.

—

Manuel de León (CSIC, Fundador del ICMAT, Real Academia de Ciencias, Real Academia Canaria de Ciencias, ICSU)

[…] el Canal Real de Dublín cuando tuvo la inspiración que cierra su teoría de los cuaternios, y que deja grabada en las piedras del puente de Brougham. William Hamilton y su esposa Helen […]

Excelente este contenido de historia y ciencia, desearía me enviasen información sobre este tipo de hechos ocurridos en el mundo, gracia.

les escribo desde Lara, Venezuela

Looking for best Accountant St Neots ? We are Experienced finance professional with a background in various industry sectors, including the service sector, construction, retail and manufacturing. Working up through the different levels in finance from the very bottom to a qualified accountant with over 25 years experience. Because of this, I understand how difficult it can be for clients with regards to finance and the necessary HMRC compliance and keeping on top of changes, for example Making Tax Digital.