![]()

La naturaleza es buena, contiene cosas útiles como las alas; más no es perfecta se indica en el párrafo ducentésimo sexagésimo noveno de El Origen de las Especies

Nos encontramos ante uno de esos párrafos que se explican y se justifican por sí mismos y que bien pudieron haber causado el ataque de risa que mencionaba Sedgwick:

If I did not think you a good tempered & truth loving man I should not tell you that. . . I have read your book with more pain than pleasure. Parts of it I admired greatly; parts I laughed at till my sides were almost sore; other parts I read with absolute sorrow; because I think them utterly false & grievously mischievous– You have deserted– after a start in that tram-road of all solid physical truth– the true method of induction. . .

269

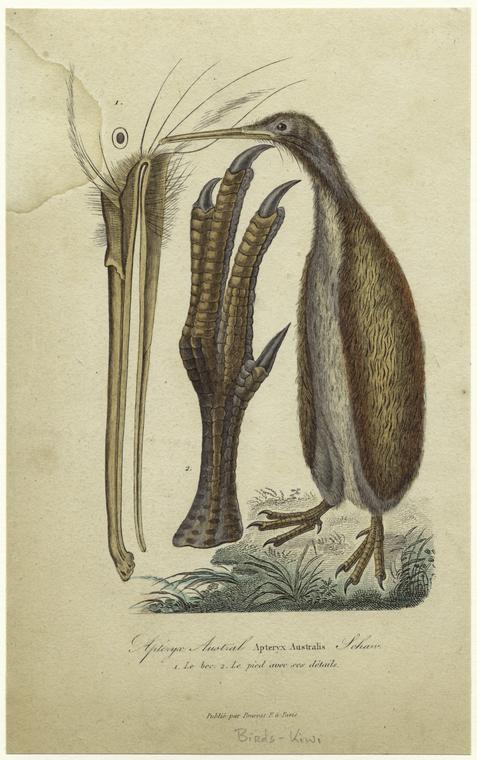

If about a dozen genera of birds were to become extinct, who would have ventured to surmise that birds might have existed which used their wings solely as flappers, like the logger headed duck (Micropterus of Eyton); as fins in the water and as front legs on the land, like the penguin; as sails, like the ostrich; and functionally for no purpose, like the apteryx? Yet the structure of each of these birds is good for it, under the conditions of life to which it is exposed, for each has to live by a struggle: but it is not necessarily the best possible under all possible conditions. It must not be inferred from these remarks that any of the grades of wing-structure here alluded to, which perhaps may all be the result of disuse, indicate the steps by which birds actually acquired their perfect power of flight; but they serve to show what diversified means of transition are at least possible.

Si se hubiesen extinguido una docena de géneros de aves, ¿quién se hubiera atrevido a imaginar que podían haber existido aves que usaban las alas únicamente a modo de paletas, como el logger-headed duck (Micropterus de Eyton), o de aletas en el agua y de patas anteriores en tierra, como el pájaro bobo, o de velas, como el avestruz, o prácticamente para ningún objeto, como el Apteryx. Sin embargo, la conformación de cada una de estas aves es buena para el ave respectiva, en las condiciones de vida a que se encuentra sujeta, pues todas tienen que luchar para vivir; pero esta conformación no es necesariamente la mejor posible en todas las condiciones posibles. De estas observaciones no hay que deducir que alguno de los grados de conformación de alas a que se ha hecho referencia -los cuales pueden, quizás, ser todos resultados del desuso- indique las etapas por las que las aves adquirieron positivamente su perfecta facultad de vuelo; pero sirven para mostrar cuán diversos modos de transición son, por lo menos, posibles.